Gummo (1997)

Spring 2016 saw the graduation of the latest set of students from the BFI Film Academy, our UK-wide scheme offering opportunities to filmmakers aged 16-19 to take their first steps in the film industry. Some of the best films made through the BFI Film Academy are available to watch on BFI Player. They are made by the latest in a long line of filmmakers who started very young. Some made some incredibly accomplished feature films aged 25 and under.

Most filmmakers cut their teeth making short films. Occasionally they make a masterpiece. Fireworks (1947), a homoerotic fantasy made by Kenneth Anger when he was 17, is one of the key works of queer cinema. Often these early shorts show the birth of a style that would be refined in later works. Hag in a Black Leather Jacket (1964), made by a teenage John Waters, displays the bawdy humour that would be embraced in his later cult classics Pink Flamingos (1971) and Serial Mom (1994). A 15-year-old Peter Jackson made The Valley (1976), a fantasy film influenced by stop-motion pioneer Ray Harryhausen, made decades before the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

It’s unusual to make a great short film aged 25 or under, but to make a feature film at such a young age is rarer still. Some renowned directors made their debuts in their early 20s, such as John Ford, who had made several westerns by his 25th birthday, and Ron Howard, whose Grand Theft Auto (1977) was released when he was 23. The 1967 film Who’s That Knocking at My Door was described by critic Roger Ebert as “a great moment in American movies” – it was the feature debut of a director named Martin Scorsese, just 25 when the film was released.

10 to try

Each of the recommendations included here is available to view in the UK.

We hope the alumni of the BFI Film Academy will follow in the footsteps of these young filmmakers, whose talent blossomed at such a young age. Here is a selection of some the greatest works of directors who were 25 or younger during the production of the films.

Alex Davidson

Citizen Kane (1941)

Director Orson Welles

Making your first movie these days is often a story of guerilla tactics and maxed-out credit cards – and, in some respects, that’s Orson Welles’s fault. Invited to Hollywood on the strength of a barnstorming career in theatre and radio, Welles was given creative carte blanche and a budget of $100,000 to make his first feature, which – after an abortive attempt to bring Conrad’s Heart of Darkness to the screen – became Citizen Kane.

Boundless in its invention and ambition, Welles’s debut feature is the story of how money and power corrupt a midwestern boy with great expectations who grows up to be a newspaper baron. Both a red rag to real-life press tycoon William Randolph Hearst and a work of apple-cart-upsetting modernism to strike fear into the hearts of Hollywood’s studio execs, Citizen Kane ensured its prodigious director never enjoyed the same freedoms again, as the system that once courted him now attempted to get the genie back in the bottle. Often voted the greatest film ever made, it remains a beacon of inspiration for filmmakers, even though it has led bankrollers to eye brilliant young men suspiciously ever since. On its premiere on 1 May 1941, Welles was 25.

Samuel Wigley

Before the Revolution (1964)

Director Bernardo Bertolucci

The young directors of the French new wave were themselves into their late 20s and early 30s when they made their own first films, but the lesson was there: by shooting on the streets with natural light, lighter cameras and a free-form, more improvisational style, filmmaking was now more accessible – and potentially more personal – than ever before.

Parma-born Bernardo Bertolucci felt that impact like a bolt from the blue, getting his own directorial debut, the flashback crime story The Grim Reaper (1962), off the ground when he was just 21. International acclaim followed, with some of the credit going to co-screenwriter Pier Paolo Pasolini, but his second film was all his own. Released when he was 24, Before the Revolution relays the sentimental education of a young Marxist student battling his discontent with the social order, while also breaking sexual taboos by falling for his own aunt. Very much a young man’s film in its existential questioning and romantic pessimism, Bertolucci’s classic precociously takes the temperature of youthful unrest that would violently erupt later in the 60s.

Samuel Wigley

Witchfinder General (1968)

Director Michael Reeves

Horror is a popular genre for young filmmakers. Sam Raimi made splatterfest The Evil Dead (1981) when he was just 22. But few have hit as hard as Witchfinder General, directed by 24-year-old Michael Reeves, which has cemented its reputation as one of the best horror films ever made. It stars Vincent Price as Matthew Hopkins, the witch-hunter responsible for the deaths of hundreds of women in 17th-century Britain, who travelled the country to rout out women he believed were guilty of witchcraft, then sentenced them to death. It was filmed in various locations across East Anglia.

Price had a reputation for overacting, and had given many over-the-top performances in campy horror films since the early 1950s. Here, he gives a chillingly believable performance as a man motivated by sadism and avarice. Reeves had previously directed horror films of varying quality, including the interesting The Sorcerers (1967) starring Boris Karloff, but none were as potent as Witchfinder General. Sadly, he died of a barbiturate overdose just a few months after the film’s release.

Alex Davidson

Je tu il elle (1974)

Director Chantal Akerman

Chantal Akerman, who died in 2015 aged 65, must have come into the world with a fully formed, radical vision of experimental feminist cinema. At 18 she made her first short film, the deliciously dark Saute ma ville (1968), a powerfully subversive take on the frustratingly limited experience of being a young woman.

Likewise, Akerman’s first feature, Je tu il elle, is astonishingly accomplished. She directs herself as the mesmerising centre of this film. We see her first in a clinical, stripped-back misery that is so extreme that it begins to border on comical while also being deeply unsettling. Finally, Akerman’s protagonist takes to the road and has two sexual encounters – first with a strange man she hitches a ride with and next, a gloriously protracted but unsensationalised lesbian sex scene with a former lover. Stark, wise and unlike anything else; to spend time with the film is a gift. Her next, and most famous, film, the four-hour Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), was also out on release before Akerman turned 25.

Nazmia Jamal

Straight out of Brooklyn (1991)

Director Matty Rich

Filmed in Brooklyn’s Red Hook housing project, Straight out of Brooklyn shows us the tough day-to-day existence of teenager Dennis Brown (Larry Gilliard Jr) and his family. Kept awake by his alcoholic father’s late-night violence, Dennis decides he will take his family out of the ghetto the only way he knows, with a gun and stolen drug money.

Despite its gangster plotline, Straight out of Brooklyn owes more to the social realist work of Charles Burnett (Killer of Sheep, 1977). Using simple scenes, constructed using a handful of shots and minimal edits, writer-director Matty Rich builds a series of vignettes that slowly reveal the frustrations of life in the ghetto for the dispossessed Brown family. George T. Odom’s depressed patriarch drags his family into a never-ending cycle of guilt and violence, while Dennis deludes himself that a quick fix robbery will remedy their desperate situation. Rich was just 17 when he wrote the film’s screenplay and went on to direct it aged 19. Budgeted via credit cards and public donations, it became the winner of the Special Jury prize at Sundance.

Dylan Cave

Boyz N the Hood (1991)

Director John Singleton

After causing trouble at school, Tre Styles is sent to live with his father (Larry Fishburne) who tries to steer the teenage Tre (Cuba Gooding Jr.) away from the brutalities of Los Angeles street life. John Singleton directed his highly praised debut feature, Boyz N the Hood only four months after graduating from the film writing programme at USC. His Oscar-nominated screenplay was drawn from the experiences of growing up in South Central LA and he brings the neighbourhood to vivid life by filming on the streets and boulevards where he’d lived as a child.

Boyz N the Hood is a feature of many debuts, with Ice Cube and Morris Chestnut in their first roles. It also launched Cuba Gooding Jr and Nia Long into the mainstream. But it’s Singleton’s first-timer achievements that are most remarkable. When the film was Academy Award nominated for best director, it made Singleton the youngest person ever nominated in that category, and the first African-American ever to be put up for the award. Not bad for a 22 year-old.

Dylan Cave

El mariachi (1992)

Director Robert Rodriguez

Famously shot for just $7,000, much of which was raised by its director taking part in experimental drug testing at a clinic in Texas, the then 23-year-year old Robert Rodriguez’s first film got him noticed by Columbia Pictures, who then distributed the film at far greater expense than its original production costs. The rest, of course, is history: Rodriguez since buddied up with Quentin Tarantino to make From Dusk till Dawn (1996), Sin City (2005) and the Grindhouse double-bill (2007), as well as remaking/continuing the El mariachi saga with Desperado (1995) and Once upon a Time in Mexico (2003).

Revisited today, the original retains its tang, arguably distilling more real flavour than many of Rodriguez’s more polished later efforts. Shot on grainy 16mm, using wheelchairs for dollies, it’s a pacy tale of mistaken identity in which the eponymous guitarist finds himself on the run from a vicious drug lord and his cronies. True, $7,000 didn’t buy much in the way of characterisation, but El mariachi is like a thrift-store Sergio Leone movie, with charm, swagger and wry humour to spare.

Samuel Wigley

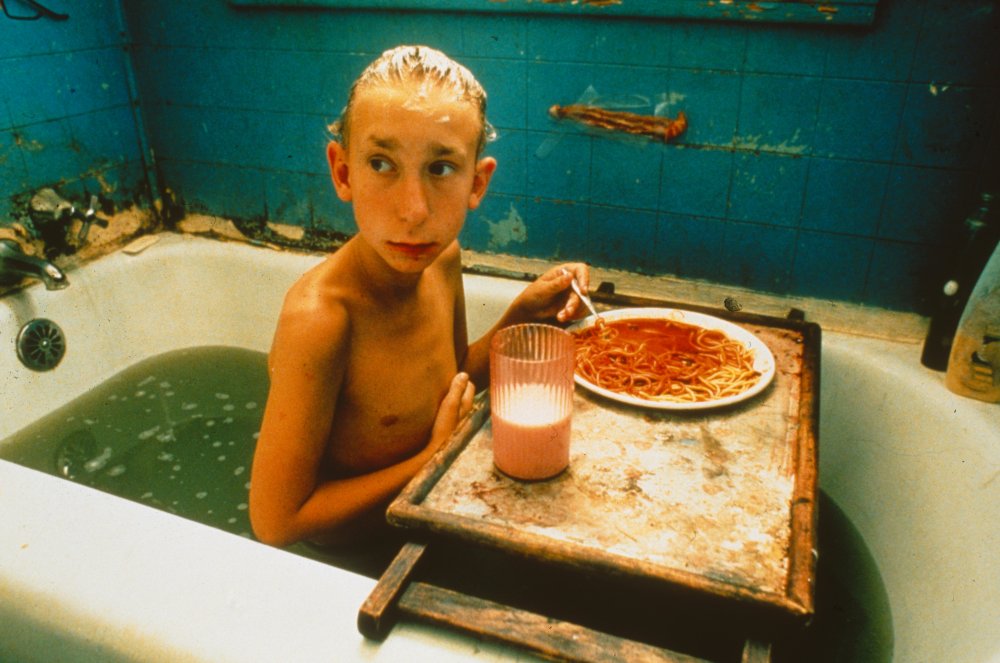

Gummo (1997)

Director Harmony Korine

There is a rumour that the set of Harmony Korine’s first feature was so outrageously filthy that crew members demanded hazmat suits (meanwhile, Korine and his DoP Jean-Yves Escoffier reportedly wore white y-fronts and flip-flops). Just 23 years old when he made Gummo (four years after writing the Larry Clark-directed Kids at the tender age of 19), Korine burst onto the American indie scene with one of the most pleasingly weird debuts in recent history.

A love-letter to small-town Americana, encrusted with spit (and other unsavoury fluids), Gummo works less as a linear narrative and more as a series of loosely-connected vignettes about the bizarre teenaged residents of Xenia, Ohio. Among Korine’s oddball assembly: glue-sniffing cat poachers, a potty-mouthed toddler dressed as a cowboy, and an accordion-touting boy with a permanently attached pair of pink rabbit ears. His style is almost documentarian and his interest in these people – a mix of actors and people he grew up with – is probing but genuine, his gaze kindly.

Simran Hans

The Apple (1998)

Director Samira Makhmalbaf

In Iran, Ghorban Ali Naderi became an object of national disgrace when the media broke the story of how he, alongside his blind wife, had kept his two daughters locked up from society for 11 years. The case opened up a debate on women’s rights, and attracted the attention of 17-year-old Samira Makhmalbaf, daughter of celebrated Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf. She made a film about the family and, in her most audacious decision, cast the real-life father, mother and two daughters, who play themselves in The Apple.

It’s a deceptively simple tale, which explores not just women’s role in society but also acts as a symbol of how Iran was at a crossroads between the religious oppression that helped isolate the country on the national stage and the opportunity to engage the wider world. It may be the best film ever made by a teenager. Samira’s younger sister, Hana Makhmalbaf, also started making films impressively young, directing the documentary Joy of Madness (2004), when she was 14, before making her acclaimed feature Buddha Collapsed out of Shame in 2007.

Alex Davidson

Heartbeats (2011)

Director Xavier Dolan

Xavier Dolan made an astonishing five feature films between the ages of 17 and 25, from his impressively assured debut I Killed My Mother (2009) to his award-winning melodrama Mommy (2014). His second film, Heartbeats is a sharp, often funny tale of two friends (Dolan and Monia Chokri), who both fall hard for a charismatic pretty boy (Niels Schneider) but can’t work out whether he is gay or straight, and compete for his affections to the detriment of their friendship.

The acting is top notch, with Schneider especially well cast as the arrogant object of lust, alternatively alluring and punchable. It’s also a visually beautiful film, appropriately high on artificial attraction, which would be expanded on in his epic drama Laurence Anyways (2012), starring Melvil Poupaud as a trans woman, and Tom at the Farm (2013), an unnerving psychological thriller.

Alex Davidson

-

Talks, interviews and trailers

Interviews from the programme sections, awards, news, red carpet and festival screenings.