from our March 2012 issue

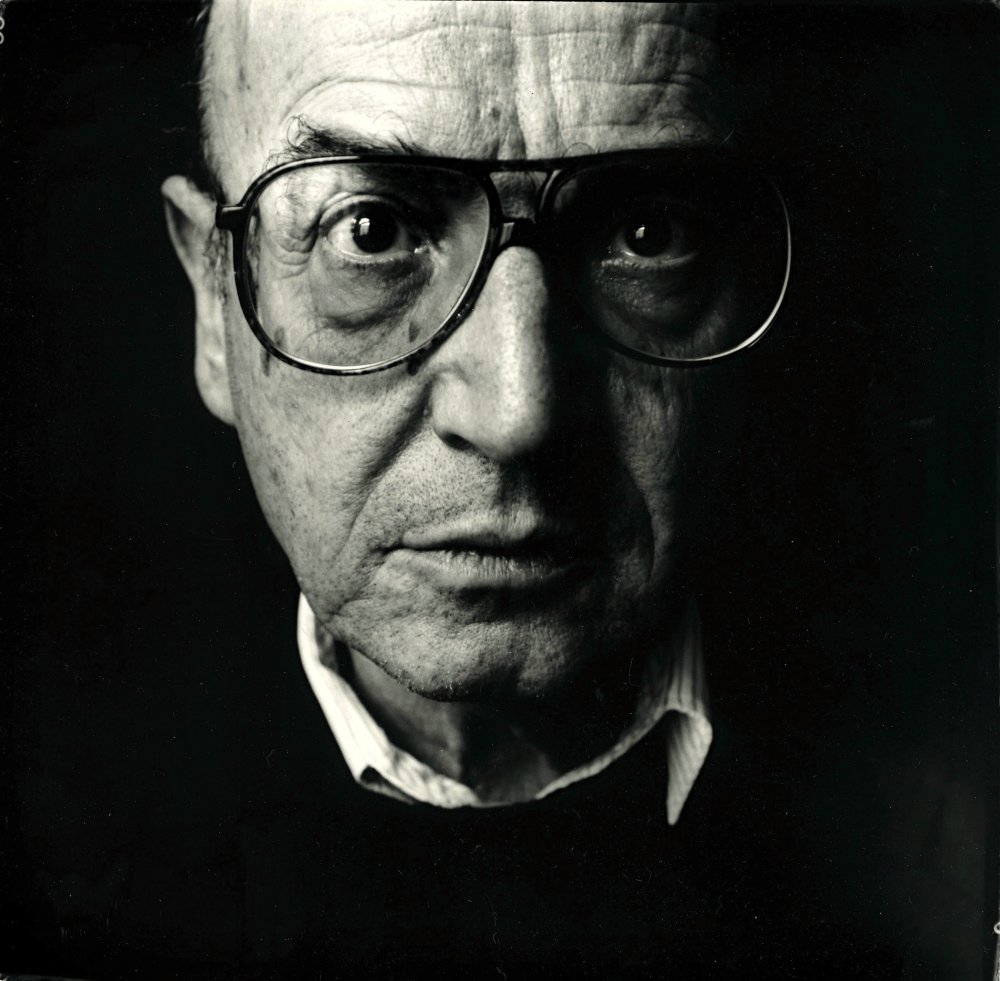

One of the last great monumentalists, Greek master Theo Angelopoulos was as much a world-builder as he was a Promethean image-maker – in order to stop your heart, he would move mountains, flood towns, orchestrate entire cities. Dead suddenly, as productive 76-year-olds should never die – hit by a motorcycle on location – Angelopoulos was an entire nation’s sole serious claim to cinematic posterity, but more vitally he was one of the irrepressible horsemen of art-film apocalypse, joining the ranks of Tarkovsky, Kalatozov and Jancsó, and helping to transform a popular vehicle for telling stories into a real-time relationship with the epically impossible.

In Western Europe particularly, where memory of the past weighs on life like cloud cover, the long, spatially expressive tracking shot enveloping whole landscapes and huge chunks of social phenomena has been an important way to shape cinema – and nobody could stride the stride like Angelopoulos. Whereas Tarkovsky’s moody set-ups were metaphysical questions growing less answerable the longer they became, Angelopoulos’s stock-in-trade mega-shots are best read as tangible translations of history into breath holding visual experience. Few other filmmakers ever dared to employ such elaborate mise en scène, but fewer still used the aesthetic to express overwhelming ideas about nationhood, justice and mass consciousness. Time and titanic scale were his weapons, turning the wholesale tragedies of Greek and Balkan life in the 20th century into journeys without end.

After art school and apprenticeship under Jean Rouch, Angelopoulos started out as a journalist and film critic. When the left-wing newspaper he wrote for was closed down following Greece’s 1967 coup, he started making films. Reconstruction (Anaparastasi, 1970) was a sociopolitically loaded if low-boiling beginning, but The Travelling Players (O thiassos, 1975) marked a gargantuan upgrade in rigour, ambition and scope, taking almost four hours (but only about 80 shots) to limn the years 1939 to 1952 and the travails of the titular acting troupe as they roam around the country and fail to perform together under various oppressive regimes and conditions.

This was the filmmaker’s first pioneering use of first-person testimony, delivered straight to the camera by the beleaguered characters, and this penchant for pungent reflexive slippage persisted in later films, which often portrayed years of tumultuous story passing by in the course of a single lengthy take. Quite possibly the most complexly conceived political film ever made, The Travelling Players instantly established Angelopoulos at global festivals, and forged an elliptically subversive way ahead.

Still, it wasn’t until 1988, with Landscape in the Mist (Topio stin omichli), that the full force of what Angelopoulos was capable of became apparent to world audiences. This epiphany was for many not only the greatest European film of the 1980s but also a redefinition of the art film as an ordeal by sympathy, monolithic visions and effortless metaphoric torque. From the giant statue’s hand rising from the sea to the catatonic huddle on a snow-shrouded highway, any single scene could change your life, or at least what you expect from cinema. A single, lengthy shot of a parked truck, while catastrophically upsetting, might also be the sharpest critique of viewer omnipotence ever created. If you’ve seen it, you’ll remember it forever.

This was not, in any case, a Greece we were familiar with; his vision of his country reflected the desolation of its political sufferings, and the trauma of its neighbours. In the 1990s, Angelopoulos became a fixture at Cannes awards ceremonies with his ‘trilogy of borders’: The Suspended Step of the Stork (To meteoro vima tou pelargou, 1991), Ulysses’ Gaze (To vlemma tou Odyssea, 1995) – which controversially missed the Palme d’Or – and Eternity and a Day (Mia eoniotita ke mia mera, 1998) – which won it. Each film follows a weathered, ageing pilgrim (Marcello Mastroianni, Harvey Keitel and Bruno Ganz, respectively) searching for lost dreams on the refugee edges of the modern Balkan nightmare.

One is tempted by now to say simply that anyone not awake or attentive to the eloquence and stupendous force of Angelopoulos’s desperate cathedrals leaves him or herself out of one of the medium’s great experiences – great in terms of both immersive exhaustion and symbolist frisson. The trilogy is not only ravishingly powerful but, as a study of modern social stress, sociopolitically necessary. Individual segments – the cross-river wedding scene in Stork, the monolithic Lenin-statue chunks barging down the river in Ulysses – could stand as galvanic masterpieces on their own.

Shooting in the farmlands outside Athens, Angelopoulos was wrapping up another, folksier trilogy – coming after The Weeping Meadow (2004) and The Dust of Time (2009) – when he died in January. The film he was working on, The Other Sea, pertained to the contemporary debt crisis in Greece, but how Angelopoulos might have framed this reality in relation to the texture of Greek history he couldn’t resist unraveling may now, tragically, be only a known unknown.