A bit like a rock ’n’ roll version of Sundance, the South by Southwest Film Festival – better known as SXSW – started as a ‘film and multimedia conference’ alongside an already established music festival in 1994 and has been growing in scope and significance ever since. The music festival still flourishes and ‘multimedia’ has become ‘interactive’. The film festival, meanwhile, retains strong links with its siblings: the first time I went, in 2011, a wristband acquired while standing in line for a documentary turned out to be the entrance ticket to an impromptu gig by Foo Fighters.

SXSW Film Festival 2017 ran 10-18 March 2017.

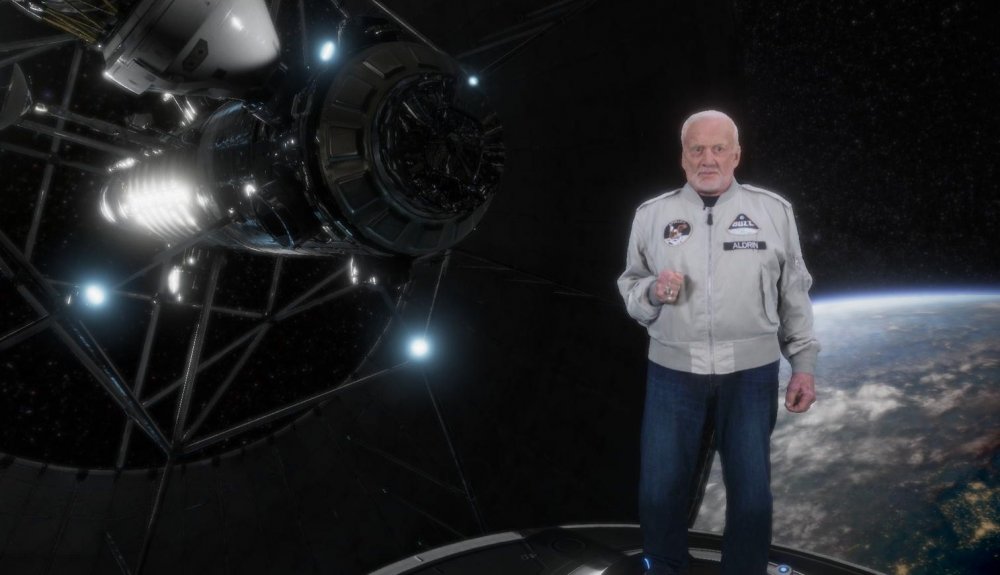

This year, sadly, I had to make do with a four-and-a-half-hour doc about the Grateful Dead, which turned up some interesting stuff in the early years but too often resembled the visual equivalent of a late-period Jerry Garcia solo. On the film-plus-interactive front, an entire floor of the downtown Hilton was given over to virtual reality projects ranging from experimental short films to Buzz Aldrin’s Cycling Pathways to Mars, in which a hologram of the 87-year-old astronaut takes viewers on a trip to the Red Planet.

Buzz Aldrin’s Cycling Pathways to Mars

Maybe ‘viewers’ is not the right word – evidence yet again that the basic terminology of film debate, starting with the world ‘film’ itself, no longer represents what is going on. Indeed, SXSW may well be the future, with its cross-media platforms and its hint that, soon, we will all access film like we access music: on demand.

Indies on demand

Basics first, however. This year’s film festival featured 85 world premieres, mainly from the US, crammed into five main venues, with a queuing system boasting that uniquely American combination of the laid-back and the strictly regimented. As it is, my basic daily timetable consisted of eight hours of films and four hours of queuing, with the occasional mad dash to a shuttle bus serving the outlying movie theatres. Austin likes to pretend it’s a walkable city; but it ain’t.

What SXSW really revealed this year is that American indie cinema and the country’s network of pay-TV companies and VOD platforms have gone way beyond the flirtation stage and are now firmly in bed with one another. Netflix and Amazon Studios logos seemed to pop up before every other film, while networks such as Showtime and HBO plastered the town (and the shuttle buses) with upcoming series, several of whose pilot episodes were screened at the Festival.

It is too soon to tell whether this is an arranged marriage or a love match, but it is significant on two levels: first for the business plan it embodies and second for the content of the films thus made. For a young American filmmaker with a project that doesn’t involve CGI, a couple of prequels or a bankable star, Netflix and Amazon are two of very few doors to knock on, given that the US has virtually no public funding for film. Soon it will have even less, following the Trump administration’s promise – announced during SXSW – to abolish PBS and the National Endowment for the Arts (the latter established, appropriately enough by Texas’s own Lyndon B. Johnson). This link-up between indie filmmakers and VOD platforms is similar to the way in which the record companies signed up bands in the heady days of the 1960s and 70s, but without the long-term commitment a record deal theoretically entailed.

It is a deal which comes with a trade-off, albeit one which most US indie filmmakers will probably be unaware they are making: in return for the production and distribution support (which may include a limited theatrical release before it goes on demand), the filmmakers deliver an audience-friendly film wrapped in a traditional narrative. Edgy, yes. Personal, no.

The result is usually either genre (there are a lot of horror films at SXSW) or issue-based content, by which I mean films with a story sculpted around a social or psychological issue. Not that dissimilar, in fact, to the Movies of the Week that the US networks used to churn out. Individual voices are homogenised; experiment is rare.

Rape revenge/recovery

M.F.A. (2017)

Rape was one issue that recurred in this year’s SXSW films, leading to lurid revenge in MFA, directed by Natalia Leite, in which a raped art student tracks down those who committed similar attacks on her friends and classmates, then despatches them with clumsy but lethal determination, much as in the 1976 shocker Lipstick.

The Light of the Moon (2017)

The Light of the Moon, meanwhile, directed by Jessica M. Thompson, takes a much less Rambo-ish approach, exploring one by one the stages along the route to recovery for another rape victim (a stellar performance by Stephanie Beatriz).

Documentaries

Inevitably – or is that just because I am European? – the most interesting films at SXSW this year were those which either avoided the ‘this is a film about x’ route; found something new to do with genre; or were documentaries which really came to grips with their subject matter.

Kim Dotcom: Caught in the Web (2017)

Most powerful among the latter was Kim Dotcom: Caught in the Web, directed by New Zealander Annie Goldson, telling the story of the flamboyant German-born computer geek who was prosecuted in NZ for building a Napster-style download system for movies and other content. Goldson pulls together an extraordinary amount of material, including some jaw-dropping police footage of a raid on Kim’s mansion. She doesn’t judge, but there is certainly more than one villain in her film.

The Work (2017)

Equally fly-on-the-wall (none of the three docs discussed here used voiceover, although all used captions) was The Work, directed by Jairus McCleary and Gethin Aldous, which won the Jury Prize. Shot almost entirely inside Folsom Prison, it follows a four-day group therapy session which is loud, confrontational, frequently violent and (according to an end caption) actually works.

METH STORM: Arkansas USA (2017)

No such positive outcome is to be found in METH STORM: Arkansas USA, directed by Brent and Craig Renaud (the caps are theirs), which charts the effects of cheap methamphetamines on an impoverished rural community in Buren County, Arkansas. The Renauds’ cameras focus on one family which is slowly destroyed by the drug. They offer equal access to the Arkansas police who try, often just as lethally, to prevent its use. The cameras never look away, even during the most extended of searches for a usable vein, leaving us with the overwhelming impression of a descent into hell, which the users are powerless to stop.

Features

Tragedy Girls (2017)

Among the features I was able to see given the queuing/viewing schedule mentioned above, two broke decisively free of the cookie cutter. Excitingly, both are first features. Possibly the most subversive genre movie since Scream, Tragedy Girls, directed by former editor Tyler MacIntyre, follows a pair of female high-school seniors who use social media to create a career for themselves as serial killers and set about offing rivals, fellow students, another serial killer and, in a dizzying, Carrie-like climax, most of their fellow Prom-goers. With sufficient gore to satisfy slasher fans and more than enough jokes to maintain the energy, Tragedy Girls is the work of a director who deserves to go far.

Hot Summer Nights (2016)

So, too, does Elijah Bynum, a former assistant at CAA, whose screenplay for Hot Summer Nights was picked from the 2013 ‘Black List’ (the annual survey of Hollywood’s ‘most liked’ unproduced scripts). With Peter Farrelly as executive producer and a pitch-perfect cast headed by Maika Monroe (It Follows), Timothé Chalamet (Call Me By Your Name) and rising British star Alex Roe, Hot Summer Nights quickly overcomes its clunky title with a voiceover that lies somewhere between Carson McCullers and Quentin Tarantino, and a coming of age story which bites off far more than it ought to be able to chew, but succeeds in being both intimate and epic. The setting is Cape Cod; the tone starts off light and funny, but gradually darkens as a massive storm approaches the coast. Bynum’s screenplay rarely stumbles – although it could lose ten minutes towards the end – and the film recalls Manchester by the Sea in its ambition and its ability to create and portray a large number of interrelated characters and incidents. I’d be very surprised if we don’t hear more of Bynum soon.

Paris Can Wait (2017)

Not all the filmmakers at SXSW were young and unknown, however. Elena Coppola, 81, showed up with her feature debut, Paris Can Wait, a sweet, food-obsessed road movie whose roads all lead through picture-postcard scenery. Diane Lane plays the wife of a workaholic film producer (Alec Baldwin) – no prizes for guessing the model – on a meandering journey from Cannes to Paris in the company of a Frenchman the like of whom we haven’t seen on the screen since Gigi – all suave flirtation, gastronomic expertise and extensive knowledge of local culture. Introducing the film, Coppola admitted she had never directed before and overcame the problem by taking a course in directing. You have to love her for that. For the film, not so much.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.