Is it a coincidence that several of the highest-profile 2D animated features of recent years have been about dying artforms? In Sylvain Chomet’s The Illusionist (2010), a stage magician struggled to find work in the rock ‘n’ roll era; Miyazaki Hayao’s The Wind Rises (2013) reflected fondly on an age when Japanese industry gave a maverick aeronautics engineer the chance to express himself; more obliquely, Ari Folman’s The Congress (2013) anticipated the demise of screen acting itself.

Ireland/Luxembourg/Belgium/France 2014

Certificate PG 93m 37s

Director Tomm Moore

Voice cast

Ben David Rawle

Conor/Mac Lir Brendan Gleeson

Granny/Macha Fionnula Flanagan

Bronach Lisa Hannigan

Saoirse Lucy O’Connell

Ferry Dan/The Great Seanachaí Jon Kenny

Lug Pat Shortt

Mossy Colm Ó Snodaigh

Spud/bus driver Liam Hourican

young Ben Kevin Swierszcz

Dolby Digital

In Colour

[1.85:1]

Part-subtitled

UK release date 10 July 2015

Distributor Studiocanal Limited

► Trailer

The Secret of Kells, Tomm Moore’s 2009 debut feature, adopted a similar premise. With its fictional account of the genesis of the intricately illustrated ninth-century Book of Kells, which is regarded in Ireland as a national treasure, it cast a wistful eye over the lost tradition of manuscript illumination. But if the subtext was supposed to be a lament for the moribund art of 2D animation, the film’s use of that medium suggested otherwise. A kaleidoscopic mash-up of Mark Baker, Michel Ocelot, The Legend of Zelda videogames, German expressionism and the Insular art it celebrated, its graphic style was a thrilling reminder that 2D animation is still vital, and doesn’t have to be ‘traditional’.

The film was a minor hit, bagging an Oscar nomination and helping to jumpstart the Irish animation industry. It’s little surprise then that Moore’s sophomore feature sticks to the formula. Song of the Sea may not be about historical events, but Irish mythology is its narrative fabric, and nostalgia its dominant mood.

Song of the Sea (2014)

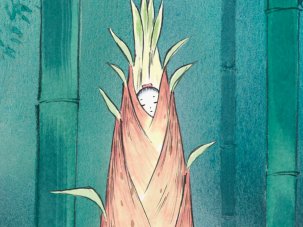

Ten-year-old Ben lives with his father and mute sister Saoirse on a remote island; their mother disappeared shortly after Saoirse’s birth. Soon Saoirse begins to display magical powers and a curious attraction to the sea: she is a selkie (a seal-cum-human in Celtic folklore) but her brother doesn’t know it yet. On their quest to help her find her voice, she and Ben encounter a merry band of legendary figures, including Mac Lir, the sea god turned to stone by his sorcerous mother. All of this is delivered with a light pedagogical touch: as well as entertain, Moore wants to impart their forgotten legends and myths to Irish children – and perhaps to international viewers, who see only leprechauns and Guinness when they look at Ireland.

The visual experimentation of The Secret of Kells has hardened into a style. The flat characters, bold shifts in palette, sudden intrusions of Flash sequences and playful manipulation of the frame are all present and correct – as is the striking use of inaccurate perspective, which makes less sense now that pre-Renaissance art isn’t the subject of the film. The novelty is gone but the technical accomplishment is greater: the background landscapes, and the clouds in particular, are more beautiful than anything I’ve seen recently outside Studio Ghibli’s work.

Song of the Sea (2014)

Indeed, the debt to Ghibli, already evident in The Secret of Kells, is glaring here – not just in the animation but also in the details of the plot. One scene evokes the Catbus ride in My Neighbour Totoro (1988), while another is practically lifted from an early encounter between Chihiro and the witch Yubaba in Spirited Away (2001). More generally, the narrative draws inspiration from folktales and the idea of the sanctity of nature.

Most intriguingly – and this quality is perhaps not so much Ghibli-esque as un-American – there are no baddies as such. The antagonist turns out to have good intentions, and ‘evil’ is shown to be relative. It’s a salutary reminder that villains are not integral to an exciting story, and that kids shouldn’t have to take for granted the dualistic worldview that Disney has done so much to cement.

Moore wears his influences on his sleeve, and Song of the Sea, more than The Secret of Kells, feels derivative in places. The story is jauntier and less convoluted this time around, and is therefore perhaps better suited to young children, if less engaging for their parents.

But comparisons with its predecessor should not detract from the fact that this is a bold and unusual film, which takes material that will be unfamiliar to most viewers and interprets it with more inventiveness than they will be used to. At a time when 3D animated films can fill seats on the strength of snazzy visuals and a couple of gags, 2D animation needs to remind viewers that it is more than a set of techniques: it is a medium in its own right, rich with unique tools of expression. To survive, it needs filmmakers with imagination. Tomm Moore is one of them.

In the August 2015 issue of Sight & Sound

Once upon a time in the west

Tomm Moore’s deeply affecting animated fantasy Song of the Sea taps in to the spirit of Studio Ghibli with its family-oriented tale of mythical sea creatures, faerie folk and a family in crisis – and, in the process, seeks to reclaim Irish folklore from the realms of tourist-tat leprechauniana. By Trevor Johnston.

-

Sight & Sound: the August 2015 issue

Pixar’s Inside Out, Song of the Sea and Halas & Batchelor in our special animation issue, plus Eden, Dear White People, new London...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.