Too often at Cannes, documentaries get ignored simply because they don’t tend to play in the main competition. This writer, for example, was one of very few critics to catch Patricio Guzmán’s Nostalgia for the Light when it played in Cannes in 2010; the press screening coincided with a much starrier event. In the case of Mahamet-Saleh Haroun’s documentary about Hissein Habré’s dictatorship, the combination of playing out of competition and having a single lunchtime press screening ensured that it played to around 50 potential reviewers at most: a great pity as it is, as one might expect, a very fine piece of work.

One of Africa’s most distinguished filmmakers, Haroun has been a regular contestant for the Palme d’or with titles like Daratt, A Screaming Man and Grigris – films dealing with issues of inequality and injustice, war and violence, revenge and forgiveness. His new movie revisits those themes in looking at the terrible damage wreaked on Chad and its people by Habré and the DDS, the political police deployed to destroy any opposition to his dictatorship in the years 1982-90. Habré, when finally overthrown, took refuge in Senegal, where he lived unpunished for a regime which resulted in the deaths of nearly 40,000 people and in horrific physical and psychological damage (not to mention dire poverty) for those who managed to survive his prisons.

After a brief prologue in which Haroun explains that he himself went into exile during the reign of terror, he introduces us to Clément Abaifouta, Chairman of the Association of the Victims of the Hissein Habré Regime – an organisation which fought a 15-year legal battle to bring the former dictator to justice. In June 2013, he was finally arrested for crimes against humanity, war crimes and torture by the Senegalese authorities.

The evidence against him, as revealed in the film, is overwhelmingly strong. Using both direct-to-camera interviews and sequences where Abaifouta converses with the complainants (and, in one instance, with a torturer remarkably reluctant to ask forgiveness of the man he brutalised), Haroun paints a painfully clear picture of the savagery inflicted on perfectly innocent people.

Save for a few graphic drawings produced for the Association’s campaign, we’re left to imagine the barbaric violence involved from the speakers’ words. It’s a powerfully effective approach, especially when we can see the consequent long-term physical damage: not just scars but blindness, deafness and other severe disabilities.

Why did the outside world not act to end such a catastrophe? Concerned primarily about Gaddafi and Libya, America and France led the way not only in distracting attention from Hussein Habré’s lethal regime but, it seems, in actually providing support for the DDS.

Haroun’s film is a harrowing reminder of what happened while the world looked away, a memorial to those who suffered and died, and a tribute to those who had enough courage, determination and hope to fight back and prosecute Habré in the courts. The trial, which began last year (the defendant refused to recognise its legitimacy), is now over; the verdict is due at the end of this month. It is the first time a former African head of state has been brought to a court of law by the people he terrorised. Haroun has done them proud.

-

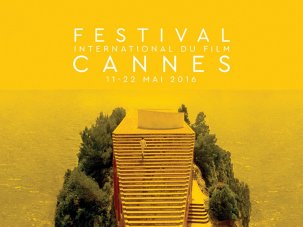

Cannes Film Festival 2016 – all our coverage

Browse all our coverage of the preeminent showcase of international and auteur cinema.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.