Of all the youngish, critically buoyed New York filmmakers to emerge over the past decade, Josh and Benny Safdie are at once the craftiest and the most reckless. They like to get away with things (cf the borderline alarming production circumstances of their 2014 junkie drama Heaven Knows What), and their movies are about characters who are similarly driven.

USA 2017

Certificate 15 101m 35s

Directors Josh Safdie, Benny Safdie

Cast

Constantine Nikas, ‘Connie’ Robert Pattinson

Nick Nikas Benny Safdie

Ray Taliah Buddy Duress

Crystal Barkhad Lennice Webster

park security guard Abdi Dash

Corey Ellman Jennifer Jason Leigh

[2.35:1]

UK release date 17 November 2017 in cinemas and on demand

Distributor Curzon Film World

goodtimefilm.com

► Trailer

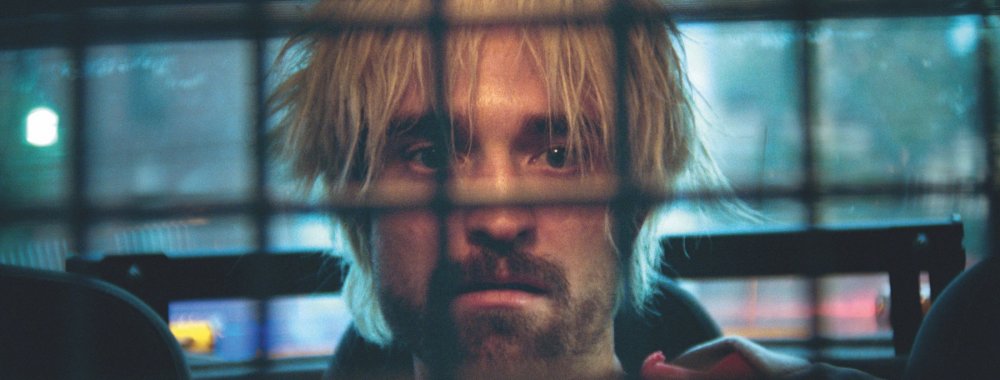

In Good Time, Robert Pattinson plays Connie, a low-level hood defined, for better and mostly for worse, by his belief that he can wriggle out of any situation if he gives it a couple of minutes’ thought. As a confidence man, he’s his own best customer. The queasy, compulsive excitement of the film lies in watching somebody who’s not quite as smart as he thinks he is living by his wits – and by the skin of his teeth.

Connie’s status as a disruptive force is established and cemented in the very first scene, when he bursts into a therapy session between his developmentally disabled younger brother Nick (played by co-director Benny) and a social worker. Not only does Connie’s intrusion cut off the dialogue between Nick and his caregiver when it seems on the verge of a breakthrough, it also up-ends the stable, shot-reverse-shot camerawork describing their exchange. His arrival doesn’t just end the session: it rewrites the film’s language. Connie is an emissary of the sprawling New York phantasmagoria that lies beyond the office walls, and Good Time’s breakneck pace and nervy, uneven rhythms – in terms of camera movement, cutting and the throbbing electronic score by Oneohtrix – are tethered to the actions of its central chaos agent.

Benny Safdie as Nick Nikas

Pattinson is tremendous here, achieving a different sort of self-effacement than in his noble supporting role in last year’s The Lost City of Z. Once again, the performance works as a disappearing act, though the point is less that an attractive movie star has believably disguised himself as a low-level hustler than that he’s hit upon subterfuge as a motif for the character. Connie operates at all times under a fog of task-oriented paranoia. The masterstroke of the script (co-written by Josh with Ronald Bronstein, who also worked on the editing) is how it takes a situation that, in almost any other film of this type, would be played for pathos – Connie’s desperate attempt to retrieve a confused Nick from police custody after the latter is arrested following a botched heist – and instead strip-mines it for every last iota of moral ambiguity. Brotherly love isn’t a higher calling here; it’s a trap that closes in on both siblings in different ways.

Nick’s incarceration essentially takes him out of the narrative, stranding Connie with what little is left of the stick-up money and stranding us with Connie, who has to rank as one of the most defiantly unlikeable protagonists in recent American cinema. What makes Good Time a slightly flummoxing viewing experience is the way the Safdies illustrate this point without insisting on it. Their style is observational, not rhetorical, and the inherent refusal to impose judgement on Connie’s actions, which quickly devolve from merely manipulative (convincing his older girlfriend, played by Jennifer Jason Leigh, to max out her credit cards to pay Nick’s bail) to truly outrageous (kidnapping an unconscious, badly injured patient from a critical-care ward), coupled with the dynamism of their presentation, creates a certain spaciousness for audience reaction. In the absence of overt ethical annotation, this supremely assured movie becomes a difficult and slippery object; one viewer’s enervating nightmare could very well be another’s good time.

So: would Good Time be improved if it were made clearer that Connie, and his habit of predatorily exploiting the people around him – particularly and most egregiously a series of African-American characters victimised in different ways along the trajectory of his rescue operation – was a ‘bad’ person? I’d say no, and not only because there are too few American movies that countenance such ambiguity. Connie may be unlikeable, but he’s not necessarily unrelatable; the sequence of deep, rocky gaps between his intentions, his actions and their consequences feel truer to life (even to lives far removed from this specific milieu) than any number of more carefully finessed antiheroes.

And the sheer multiplicity of ways the Safdies find to comment on the action visually – shooting an extended set piece in a deserted amusement park beneath a mix of neon and black light, or elevating their camera to a despairing bird’s-eye view at a fateful, decisive point – all but demolishes accusations of glib irresponsibility. Connie is a hopeless case. But his creators know exactly what they’re doing.

In the December 2017 issue of Sight & Sound

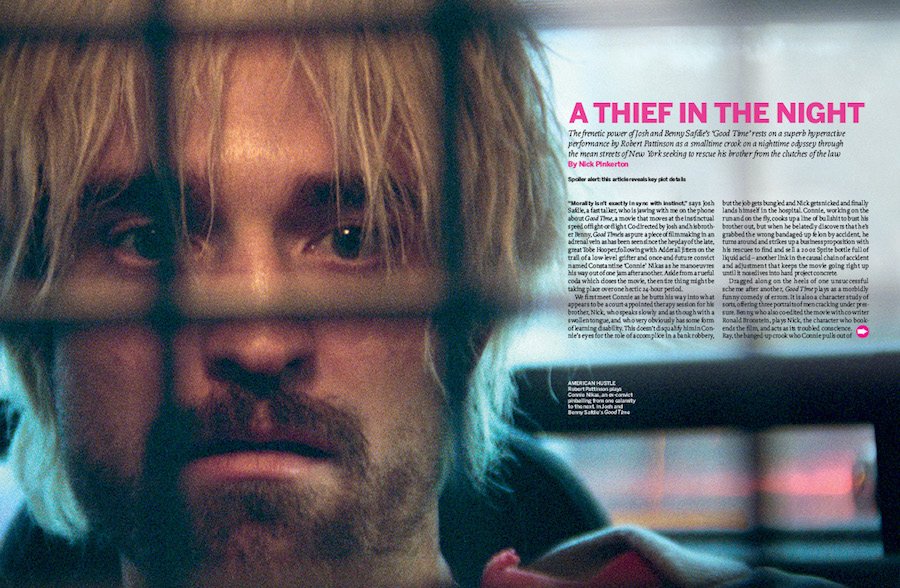

A thief in the night

The frenetic power of Josh and Benny Safdie’s Good Time rests on a superb hyperactive performance by Robert Pattinson as a smalltime crook on a nighttime odyssey through the mean streets of New York seeking to rescue his brother from the clutches of the law. By Nick Pinkerton.

-

Sight & Sound: the December 2017 issue

Robert Pattinson in in the Safdie brothers’ Good Time; plus The Florida Project; Mudbound; Gloria Grahame, Annette Bening and Film Stars Don’t Die...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.