from our December 2012 issue

P.T. Anderson’s The Master isn’t just a divisive film – it’s a divided film, a film of two portraits hung pendant. Like Anderson’s last historical fiction, There Will Be Blood (2007), which centred on the grudge match between Daniel Day-Lewis’s Daniel Plainview (commerce) and Paul Dano’s Eli Sunday (religion), The Master is written around the jockeying juxtaposition of two American archetypes, a comparison revealing real divergences as well as a national family resemblance.

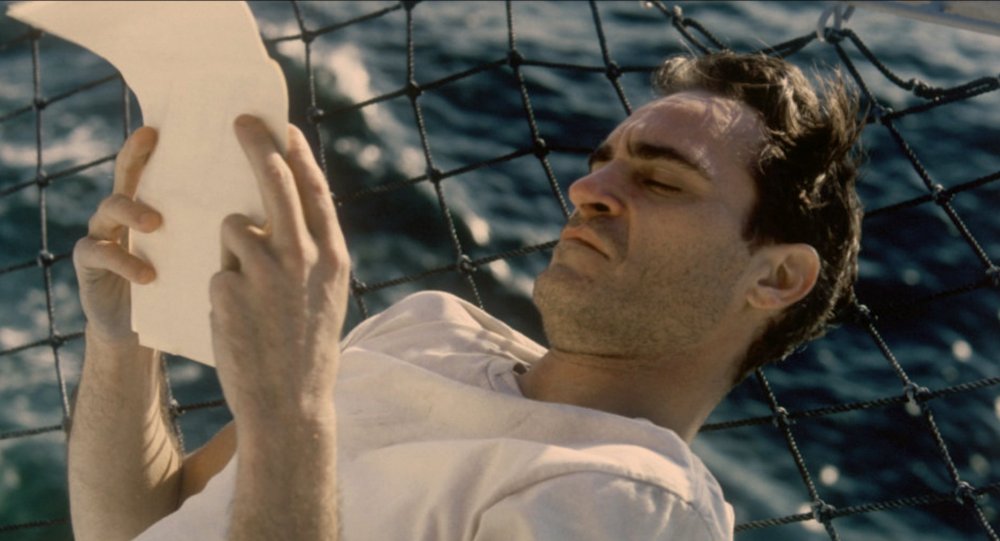

The first to be unveiled is Freddie Quell, played by Joaquin Phoenix. Quell, when we first meet him, is drawing pay from the navy, marking time on some Pacific island at the fag-end of World War II, spending the Best Years of His Life getting high on torpedo fuel, humping a woman made of sand for an appreciative audience of his mates, and pausing from macheteing coconuts to, we distinctly intuit from his screwed-up expression, contemplate chopping off some fingers. Making no apparent progress in stuffing his id back into the bottle, Quell is unleashed on the stateside civilian population.

| USA 2012 Crew Director: Paul Thomas Anderson Produced by Joanne Sellar, Daniel Lupi, Paul Thomas Anderson, Megan Ellison Written by Paul Thomas Anderson Director of Photography Mihai Malaimare Jr Editors Leslie Jones, Peter McNulty Production Designers Jack Fisk, David Crank Music Jonny Greenwood Supervising Sound Editor/Sound Design Christopher Scarabosio Costume Designer Mark Bridges Cast Freddie Quell Joaquin Phoenix Lancaster Dodd Philip Seymour Hoffman Peggy Dodd Amy Adams Helen Sullivan Laura Dern Elizabeth Dodd Ambry Childers Clark Rami Malek Val Dodd Jesse Plemons Bill William Kevin J. O’Connor John More Christopher Evan Welch Doris Solstad Madisen Beaty Dolby Digital/Datasat In Colour [1.85:1] Distributor Entertainment Film Distributors Ltd |

Landing a job as a studio photographer in an immaculate downtown department store, he swills developing fluid in the darkroom, a worm burrowed in the bright blooming rose of prosperity, memorialising the post-war cult of family life from which he’s excluded. Quell keeps his thousand-yard squint fixed on a remote heartbreak which, in a game of give-and-take revelation and obfuscation – the film’s signature manoeuvre – will eventually be ‘explained’ in a manner that doesn’t seem like a satisfactory explanation at all. (This strategy of confounding extends to the visuals: The Master was shot in 65mm and is being projected, where possible, in 70mm – classically the trappings of an epic, but Anderson has essentially made a chamber drama, shot by DP Mihai Malaimare Jr with a stiflingly shallow depth of field.)

Freddie is a great character, redolent with associations, and Phoenix does urgent, erratic work here, making him the most extravagantly ruined screen drunk since James Dean’s in Giant (1956). It’s difficult not to bring up Dean, and the legacy of Method acting generally, when discussing Phoenix’s performance, though specifically he seems to be channelling Dean’s spiritual big brother Montgomery Clift – it’s in the wiry, vexed black brows, the concave chest, akimbo arms and Ichabod Crane elbows; it’s even in Phoenix’s harelip-ish scar and half-snarl, suggesting Clift’s damaged, post-auto-accident incarnation.

Regarding influences, Phoenix has stated that Anderson directed him as homework to two non-fiction films: John Huston’s 1946 report on the returning walking-wounded veterans Let There Be Light, and Lionel Rogosin’s 1956 portrait of skid row’s topers On the Bowery, both essential documents of traumatised masculinity and opting-out of mid-century America. Quell receives his own directorial coaching, however, under the tutelage of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Lancaster Dodd, who’ll guide his pupil through a number of ‘processing’ exercises to excavate past lives – exercises that resemble nothing so much as an acting-class visualisation or the dredging up of buried traumas to spill on stage.

A literal any-port-in-a-storm moment brings fugitive lone-wolf Quell aboard the yacht that’s been chartered by Dodd, a rubicund, rotund, patriarchal bon vivant who adds him to his extended family, along with wife Peggy (Amy Adams), daughter Elizabeth (Ambyr Childers) and a coterie of well-heeled followers. Dodd is lifting anchor to embark on a fundraising tour of the East Coast, pitching a programme to the dowager set which promises mastery of the passions – though it quickly becomes obvious that this is a textbook case of the physician who can’t heal himself when Dodd’s cool cracks upon having to confront a simple line of sceptical inquisition at a cocktail party, prompting him into a Tourette-like hiss of “Pig fuck”. When, further along on his tour, Dodd and Quell are hauled in by the Philadelphia police and thrown into adjoining cells, it takes very little time for both to be reduced to the same level, barking at one another through the grille that separates them until finally ‘the Master’, who’s earlier shown a smug forbearance at Freddy’s fondness for breaking wind to comic effect, gives way to animal need and turns his back to take a slash.

The third corner of the triangle is Dodd’s wife Peggy, who is revealed as something like the brains behind the throne: the ghost-writer dictating what will be Dodd’s sophomore work to him, or giving her obeisant husband a kung-fu-grip handjob over the bathroom sink, as one might give a noisy pet a treat. Given these insights into the Dodds’ conjugal bliss, Lancaster’s attachment to Freddie seems like a case of vicarious-living fascination, the sort that the tamed so often harbour for the wholly undomesticated. One thinks of comparatively shy Jack Kerouac’s worship of uninhibited Neal Cassady, since The Master is nothing if not an open invitation to plug the period’s cultural reference points into it, and as much as a Method man, itinerant Freddie’s full-tilt flight from this timid new white-collar world makes him an avant la lettre Beat poet (and he don’t even know it).

As for Dodd, he belongs to a lineage of self-styled prophets and confidence men through history – and Anderson’s filmography: there’s Sunday, blackmailing funding for his Church of the Third Revelation in There Will Be Blood, and seduction seminar guru Frank T.J. Mackey in 1999’s Magnolia. Mackey was played by Tom Cruise, the most public face of Scientology, whose early years are clearly the model for Dodd’s movement ‘The Cause’, as founder L. Ron Hubbard is the taking-off point for Dodd himself. The 2007 suicides of Jeremy Blake and his girlfriend Theresa Duncan, who had alleged persecution by shadowy Scientologist forces prior to their deaths, offer a personal connection for Anderson – Blake was the digital artist who created interstitial imagery for Anderson’s 2002 Punch-Drunk Love, a film that, like The Master’s burlesque of the classical wild-child-and-mentor tale, might be said to be ‘about’ self-regulation.

Another possible analogue for ‘Dr’ Dodd: scamming ‘Professor’ Harold Hill in Meredith Wilson’s 1957 The Music Man. In two sequences that are among the most discussed in the proliferating body of exegesis surrounding The Master, the man who pompously describes himself to Quell as “a writer, a doctor, a nuclear physicist and a theoretical philosopher, but above all… a hopelessly inquisitive man” is seen as a mere song-and-dance showbiz razzle-dazzler. In the first, as a satyr-like Dodd performs a ribald sea shanty, ‘The Maid of Amsterdam’, for a houseful of potential investors, the female members of his audience are abruptly seen without clothes. Are we witnessing an actual act of mass seduction? An X-ray-glasses hallucination from erotomaniac Quell’s addled brain? Peggy’s jealous imagination running wild? All three? In the other, Dodd softly serenades his departing protégé after their break-up with a rendition of ‘(I’d Like to Get You on a) Slow Boat to China’.

This lullaby intimacy suggests that we have been watching a same-sex love story all along, though there is little enough evidence of it in what’s preceded, beyond some playful rough-housing. It’s one of Anderson’s blind-siding gambits, which for some are proof of the filmmaker’s gun-slinging artistic bravery, though more often they seem rooted in epochal ambition turned to wild desperation – frog storms, Aimee Mann sing-alongs, doughnut-shop and bowling-alley bloodbaths or, this time around, nudie-cutie musical numbers and homoerotic lullabies. Towering standalone moments all, they are certainly impressive when first encountered, though they wobble perilously the longer one looks at them, detached as they are from any narrative undergirding.

The indeterminate spaces of Anderson’s film leave plenty of room for the viewer to fill in, making The Master easily the best movie this year to talk about. It isn’t a great film – but it has a great film rattling around inside it, the story of deadlocked Freddie Quell, a dynamic study in stasis. That paradoxical tension doesn’t animate Hoffman’s Dodd, who has much the same weakness as Plainview in There Will Be Blood: it’s a ‘revelation’ of character through reiteration of the same basic facts (Plainview’s vengeful, unscrupulous covetousness, Dodd’s perfidy and charlatanism) rather than the accumulation of multivalent perspectives, making for something as monotone as Jonny Greenwood’s hectic dogfight score. Is The Master a true faith or a cult? Is Emperor P.T. dressed to the nines, or parading around starkers? Its larger contradictions happily defy such gross simplifications, even as its conception of Dodd does not.

In the December 2012 issue of Sight & Sound

Hearts and minds

The Master may be loosely inspired by L. Ron Hubbard, but Paul Thomas Anderson’s film also draws on rich strands of philosophy, period recreation and psychological excavation, says Graham Fuller. PLUS James Bell talks to the director.