With numerous excerpts from her private diaries, myriad family photographs and significant home-movie footage (much of it shot by the lady herself), this is very much an access-all-areas feature-length tribute to Ingrid Bergman. Past experience of TV arts docs has taught us that the opening up of an artist’s family archive often comes at an editorial price, too often resulting in bland legacy management rather than genuine revisionist insight. All credit, then, to veteran Swedish critic and filmmaker Stig Björkman for surmounting the usual scissors-and-paste expectations and delivering an intimate, involving portrait of a remarkable woman who blazed her own independent path in love and on screen – a bio-doc with the complexity and texture of a drama to add to its fascinating mosaic of cherished memories and archive titbits.

Sweden / Germany / The Netherlands / Finland / Norway 2015

Certificate PG 114m 2s

Director Stig Björkman

With

participants Pia Lindström, Roberto Rossellini, Ingrid Rossellini, Isabella Rossellini, Fiorella Mariani, Liv Ullmann, Sigourney Weaver, Jeanine Basinger

Ingrid Bergman’s voice Alicia Vikander

[1.78:1]

Part-subtitled

Swedish theatrical title Jag är Ingrid

UK release date 12 August 2016

Distributor Soda Pictures

► Trailer

The overall trajectory of Bergman’s screen career is already well known. The fresh-faced Swede was one of the marquee names at home before being spotted by Hollywood, where she brought a new kind of unvarnished glamour to treasured favourites such as Casablanca (1942) and Notorious (1946).

She then caused a scandal by taking up personally and professionally with Roberto Rossellini, when both were married to other people, though a subsequent rapprochement ensued, thanks to the Oscar-winning Anastasia (1956). As the years wore on, Bergman spent much time on stage in Europe and on Broadway, and had one last filmic flourish in Ingmar Bergman’s Autumn Sonata (1978) – whose beady focus on motherhood could hardly be more relevant given what Björkman reveals here about her approach to parenting.

The bases, then, are duly covered, but what you don’t get here (and which may not please everyone) is much in the way of fresh gossip or fun facts about her best-known movies. Not terribly much at all, in the event, about Casablanca, Notorious or even 1954’s Voyage to Italy (which has always looked like scenes from the Rossellini marriage, and some confirmation might have been welcome). Overall, though, it’s hard to feel short-changed, since Björkman’s ambitions are not about looking in from the outside but rather about trying to assess how Bergman thought of herself, as revealed in her diaries and correspondence – read with a sense of hushed confidences by Alicia Vikander.

What emerges is that some of the defining events of Bergman’s life happened before she ever ventured on to a film set. Björkman grabs our attention early on with a heartbreaking diary entry from the 13-year-old Ingrid, offering a desperate plea for God to intervene in her father’s illness. Alas, he passed away shortly afterwards, in 1928, 11 years after her mother had succumbed to jaundice, leaving Ingrid with no memory of her.

In the time that remained to her dad, he took numerous photographs and home movies of his only child, instilling in her the significance of recording family life. Moving forward, we see how much time Bergman spent filming and photographing her own children and husbands. Here, however, Björkman’s film points up a fundamental contradiction: for all her determination not to let these domestic moments slip away, we sense an inherent restlessness. Professional insecurity made Bergman nervous about being out of work, and she was utterly dedicated when in it, a fact that often limited the time she spent with her kids – as valuable interviews with Pia Lindström and Isabella, Ingrid and Roberto (junior) Rossellini attest.

Intriguingly, Bergman’s diaries talk about a lonely childhood, when the acting bug was sown by the conversations she had with her imaginary friends. This sense of self-communion or self-involvement certainly comes through in the often headstrong personal decisions that shaped her life and career. Björkman is relatively sparing with actual movie clips, but anyone who’s watched Bergman’s films over the years will be familiar with the sense that she’s captivating on screen not just for that open-air beauty and confidence within her own stately frame, but precisely because she’s so much her own woman – innocent yet carnal, troubled yet with a self-preserving intelligence. As such, she’s actually quite hard to read, and we’re drawn to her even more because of it.

With so much reference material at his disposal, Björkman can’t pierce that mystery entirely, but what he does do quite elegantly is explore the mixed feelings of those four surviving children, all of whom make clear how much fun she was to be with and yet – without any sense of Mommie Dearest recrimination – also give vent to their feelings of being left behind when she was away filming, or indeed when she had moved cities to be with a new partner. Michael Nyman’s chamber-scaled score, in part a reworking of his affecting soundtrack for 1999’s Wonderland, provides a tellingly poignant undertow to the family’s to-and-fro of enduring affection and unrequited longing, all of which adds considerably to our understanding of one of the screen’s indelible icons.

In the September 2016 issue of Sight & Sound

Ingrid Bergman: always be yourself

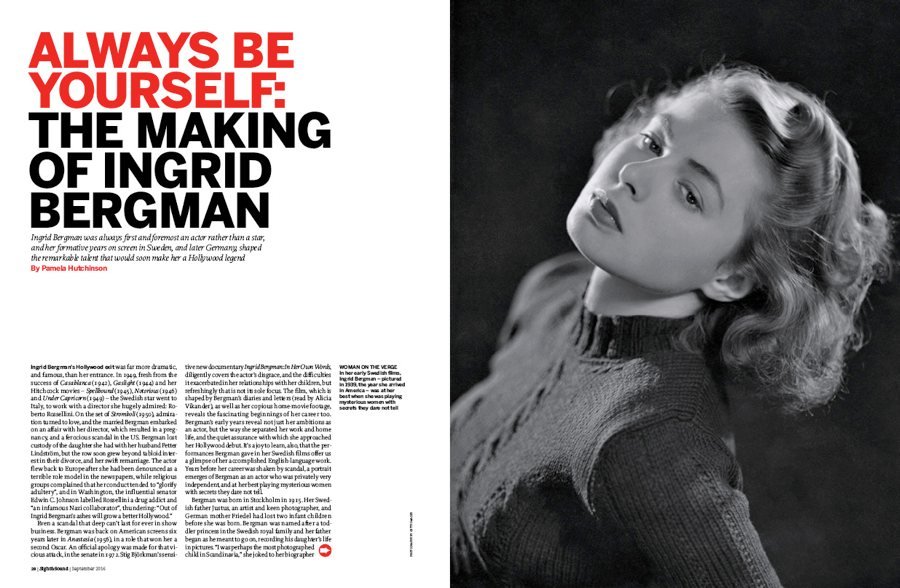

Ingrid Bergman was always first and foremost an actor rather than a star, and her formative years on screen in Sweden, and later Germany, shaped the remarkable talent that would soon make her a Hollywood legend. By Pamela Hutchinson.

-

Sight & Sound: the September 2016 issue

Isabelle Huppert in The S&S Interview, plus Mia Hansen-Løve on Things to Come, Pedro Almodóvar on Julieta, Todd Solondz on Weiner-Dog, Jaume...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.