Web exclusive

Hans Hurch

Next year the Viennale, one of the world’s most smartly curated film festivals, celebrates its 50th anniversary. Having just attended the latest edition (you can read my report in the January 2012 issue of Sight & Sound), I invited its artistic director Hans Hurch, who’s been at the helm for 14 years, to discuss the daily balancing acts involved in running a festival, the pleasures and perils of programming, and the highs and lows of contemporary cinema, in particular British and Austrian.

How long have you been running the Viennale?

For 14 years. I worked as a film critic before that for a weekly here in Vienna called Falter, and I organised a thing called ‘100 Years of Cinema’, a big project by the Ministry of Cultural Affairs in Vienna.

How many programmers do you have working under you at the Viennale?

There are no programmers. I do the whole programme. For some of the special programmes and tributes I ask people to curate, and I have a network. There are several people in different countries, but they just send me information and DVDs, or tell me about something. People who come here – critics, filmmakers, etc – recommend films to me, because they know the taste of the festival.

So you’ve seen every film in the festival?

I’ve seen 95 per cent of the programme, but I’m talking now about the new films. There are around 140 documentary and feature films, and a lot of short films.

You mention the taste of the Viennale. To what extent is that a reflection of your own taste?

I have to be careful because the Viennale is much more than my taste, it’s something different. If I made the festival according to my taste it would be 20 films each year – or maybe not even that many. There aren’t 140 really good films in a year, there are only a few. So it is my taste, but it’s also the taste of cinema – something else, something bigger.

The way the Viennale is programmed is very unusual, because I don’t have anybody who interferes, who tells me what or what not to do. If a distributor says you can show this but you have to show this too, I don’t show either. So if there’s something good about the Viennale, it’s my work, but if there’s something bad, it’s also my work.

I think a festival should be run like this, because somebody should be responsible. Because you’re responsible to the filmmakers, and a filmmaker has to make his decisions, his political and aesthetic decisions. If he starts to discuss with 20 people on the set, he won’t know how to frame. But it doesn’t mean it’s an ego thing. I don’t know how to explain it.

I don’t want the Viennale to be the Hans Hurch festival, I would hate this idea. I don’t think I’m so good or important or something. Art is not a democratic thing. At the same time it doesn’t mean it’s a non-democratic thing. It’s very difficult to explain, my own work, my own situation, because this is the only way I can do it. If it were someone else, they would do it their way.

I know it’s not normal what I have, it’s a privilege and a luxury, but we have been fighting for this. And the other thing is, as long as the festival is successful, I’m lucky. If not, it’s also me.

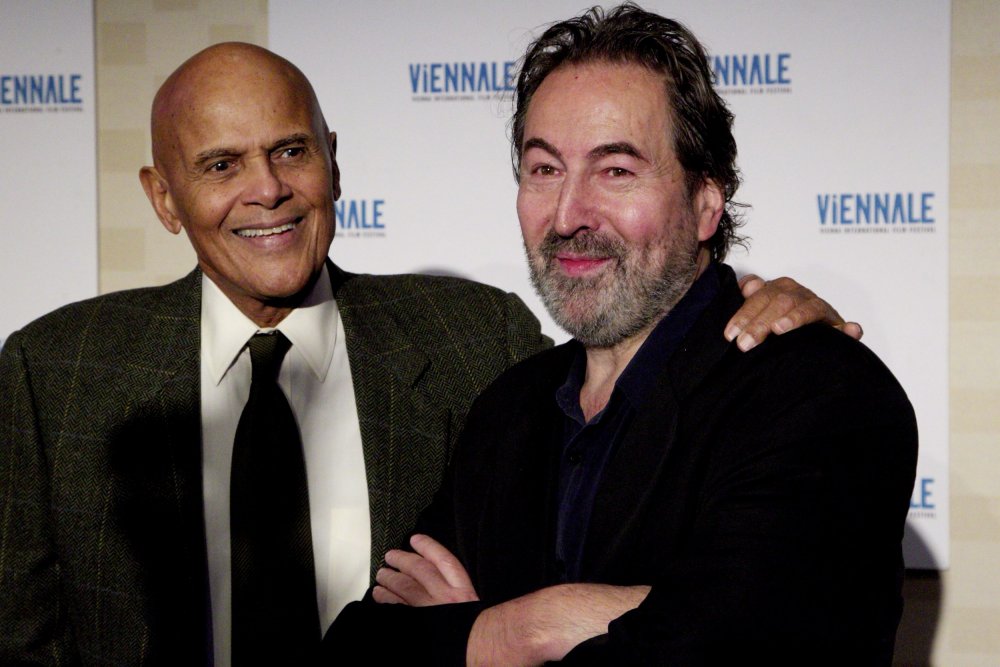

Hurch with Harry Belafonte (left)

Do you mean in terms of audience numbers? Is it successful?

It’s more and more successful, although this is also an idea that I don’t like. I really think you have to be very careful with this machine of the box office. When a festival grows, you have to be careful it doesn’t become too big. There are festivals I like very much that at a certain point were destroyed by this. Rotterdam was an incredible festival; now it’s an example of a festival that doesn’t have a heart, that does not have an artistic idea.

So what’s the ideal size for a festival?

A festival should not be too small or too big, it should be something in between, and we tried to find something that is the right size for Vienna, and we’ve been lucky with this.

At the same time it’s not a question of luck. Because we are in a situation compared with other festivals where we have enough money to work, we have very beautiful cinemas, we don’t have to use a cinema in a shopping mall. We have cinemas from different eras, all different sizes. They’re all very close to each other.

We’ve been fighting for this. They wanted to close the Gartenbau (the biggest centrepiece cinema), and now the Viennale programmes the Gartenbau the whole year. We fought for it with the city; we said they should give us some money and support and we’d take responsibility, that we wanted to programme it, during the festival and throughout the year.

What about your relationships with sponsors?

You’re always fighting against the sponsors, because they always want more and more. There are things which are absolutely taboo. For example, in the auditorium they will never get something on the screen. The sponsors are like a virus, the money is a virus, it gets everywhere, and you have to be careful. I always say that I sleep with a gun under my pillow, because you have to be aware of this all the time.

On the one hand I’m a very diplomatic guy, but on the other hand I can be very Stalinist. You have to be. I learnt this from Jean-Marie Straub. I worked for him for ten years or so, and that was a good school. I learnt not to become sentimental.

L’Argent (1983)

How would you sum up the taste of the Viennale?

I would be happy if it’s a festival that’s not doing harm to the people. It sounds very defensive, but it isn’t. There are so many things in the world that are doing so much harm, and I believe in an old leftist idea – everything you experience does something to you. So if you drink something that is not good, it won’t do you good. If you see something that is not good… Of course I’m simplifying, it’s more complicated than that – but I’m very instinctive about this, I think it’s in you. It doesn’t go through you, it’s a kind of pollution. And what I want to do is to find and show films – to be a go-between between films and the public – that are not polluting. It’s silly to say, but it’s what I think.

I react very instinctively to films. I have a problem for example with violence. There are some films here in the programme that are maybe too violent. Some of Pou-Soi Cheang’s films, and maybe Drive. I don’t like it. To show violence in a film, you have to be really good. And most violent films are just brutal, in the same way that other films are not about feelings, they’re just sentimental. There’s a big difference.

This would be a very long discussion, because at the same time you have to be fascinated by things. In a certain way you have to be fascinated by violence to do a film on violence – just like if you make a war movie or something. For me John Ford is the perfect example.

I assume you mean the lift scene in Drive?

I really thought for quite a while about showing this film precisely because of this scene. When they asked Jean Renoir when he was very old if there was anything he regretted, he said “I very often think about the rabbit we shot in La Règle du jeu. This rabbit sometimes haunts me.”

For me a film that I love a lot where there’s a lot of violence is L’Argent. It’s the most violent film, but you don’t see any violence. It’s about money, it’s about killing those people who care for you, killing them when they’re asleep at night; they hide this guy and he kills them and you don’t know why, but at the end somebody says he will be forgiven. It’s incredible; it gives me goosebumps even when I talk about it. For me this is really violent.

It’s the same with sex and love in films: it’s so difficult to do. I react instinctively to things, but of course with all that I’ve seen and learnt and done, and then I try to put it together, and if it makes a kind of sense then it’s nice.

Jean-Claude Rousseau’s De son appartement (2007)

How would you characterise the festival’s relationship with the Viennese public?

For more than 20 years, my predecessors and I have been building up a kind of relationship between the festival and the public; my idea is they should trust us, and I should trust them. So if I want to risk something, I can put films out there, and I trust they’ll be curious and want to see them, even if they maybe don’t like them. And they should have the feeling that I’m not treating them like consumers whose money I want. We’ve built this up over the years, and this is something very precious. This is something you should never gamble with. So with Drive, I asked myself, am I gambling with this a little bit?

But they’ll make up their own mind?

I know, but still it’s a situation of trust. If I go to other film festivals – and this is not a nice thing to say – out of ten films I see, there’ll be seven I don’t like. There’ll be three I like and one I really like. And my idea with the Viennale is for it to be the other way around. I would very much like the audience to like six or seven films. And this is my idea of not wasting too much of your time and your life. It’s precious. It’s not about money, it’s about your energy and your sensibility.

Your predecessor was Alex Horwath, who now runs the Film Museum in Vienna. Is your Viennale very different to the way he did things?

It was not so obvious at first, but I’m very different from Alex. Alex has more of a fan’s attitude, so he would show films by certain people – for example, Olivier Assayas. He’s a kind of a fan of some people.

But you too seem to have talismanic figures, for example Straub and Jean-Claude Rousseau?

But the funny thing is, I would not regard myself as a fan of these people. Alex is ten years younger than me, and we know each other very well. Take Mia Hansen-Løve, for example: her films are completely chichi, a little-French-girl thing. I don’t like them at all. Alex likes her, so he would show all her films.

But that very personal approach is also something very nice about Alex. He would just show the films because he liked and followed the people. And I lost some people on the way. I liked Jacques Rivette very much at a certain point, then got more and more disappointed by the things he was doing. I don’t like everything Jean-Claude Rousseau does when he’s repeating himself.

Jean-Marie Straub’s Schakale und Araber (2011)

With Straub it’s different. For me he’s Schoenberg; he’s the most important. At this point he’s a filmmaker who’s always been interesting whatever he does. It’s difficult to talk about this. Alex would say Martin Scorsese is a big filmmaker, and he is, but Straub is much bigger. Scorsese hasn’t made very interesting films for 15 years, Wim Wenders hasn’t for 20 years; the same with Bertolucci… There are so many filmmakers I’m not interested in anymore.

But with Straub there’s always something I can relate to, something that touches me. It’s something else, something alive on every part of the screen and in the voices. When I see it, it freshens me up. I know for other people it’s really boring, and I don’t want just to be the big Straub admirer. I hate this idea.

I like that the Viennale has no red carpet.

I don’t think the media is as interested in this as everyone thinks, you know. That’s my experience. First of all I’m not so fascinated by this. I know some of the so-called famous people, but it’s not for me. I don’t think it’s necessary to do it – it’s 19th century, it’s opera, it’s not modern cinema to do red carpet. But still it’s very nice to welcome someone like Harry Belafonte.

I remember when Lauren Bacall was here, for example – she’s really a star, but she doesn’t need a red carpet. She said to me just at the last moment before we walked up on stage at the Gartenbau, “Hans, you’re definitely underdressed.” It was so incredible. I said “Thank you Lauren, this is the right moment to tell me.” She was so funny and so sharp. It was like in a Howard Hawks film.

But a festival like the Viennale doesn’t need red carpet. Maybe other festivals need it – or think they need it, I don’t know. It’s their decision, but it’s not necessary to do it. For the sponsors and politicians and media I know it’s nice.

And there’s one other reason to avoid it: it costs a lot of money. There are certain things I would never do, such as private transportation. What for? These are all people who have a lot of money, and they come with ten people.

What’s the festival budget?

Very close to €3 million. Half of the money comes from the city, and the other half from sponsors and from ticket sales. So you’re not depending too much on the sponsors.

You’ve managed to last a long time in a role which at other festivals seems to have a high turnover.

But now I’m running into trouble. I’m very famous for my opening speeches. This year I gave a very political opening speech which was a big problem for the Socialist Party in Vienna. I said that in a country that is rich like Austria, there is no excuse for politicians here to be so – they’re not really corrupt, but they’ve become a political class that is really going for their own interests. It’s a kind of Berlusconi thing that gets worse and worse; you have the sense they feel no responsibility for the res publica. The next day they said I’ve signed my death sentence.

I don’t take them too seriously, but I have to be careful. At the same time, I’m not afraid of them at all.

There’s a certain kind of commercial cinema that by and large doesn’t get shown at the Viennale – and your catalogue note this year was strikingly utopian and anti-consumerist.

But I make compromises too. If you take the closing-night film, George Clooney’s The Ides of March – it’s a nice film, very well-written, but it’s a liberal American, not a radical film. And the opening film, Le Havre, too, in a different way. I programmed the Straub film, Schakale und Araber, before Le Havre, and there were 750 people in the cinema who’d never seen a Straub film. Sponsors and their wives.

I wanted them to see it, and maybe this is the idea, that there should be no special idea of cinema, you know. Not a fixed idea, no hierarchy, but that things should exist in a connection and in a tension to each other. So there are no fiction films, no documentaries, no short films, they’re just films, and you have to treat them equally, and it gives some mixture, some tension and contradiction, that becomes interesting. It becomes a kind of texture.

But I’m never planning it, I don’t think it’s something you can plan, to say ‘I’m going to make a political texture in this festival’. It comes out in certain ways. So the idea is that there’s no hierarchy in terms of commercial and non-commercial. Every film is commercial, even if it doesn’t make money.

How do you avoid becoming jaded in your job?

I really love to be surprised. It doesn’t happen very often, but it happens, and then something opens up and I’m happy. I know what I’m working for, I want to work for the film, I want to be the go-between between it and the public, and I want to have the filmmaker here as well.

This also makes me think of Straub; I learnt so much from him about films. He said to me one day: “I’ve seen a film: you have to see it.” I said, “What is it?” “He said, “Dr T and the Women, by Robert Altman.” I said, “Jean-Marie, you’re crazy.” He said, “This is an incredible film, such a clever film about America and history and about getting older, and Richard Gere is incredible.”

This is what I like, to be surprised. And he meant it. He said “Robert Altman is the most important living American director, believe me, he’s much better than Scorsese. Scorsese is neo-realist European arty-farty, but Altman is the real chronicler of America. When he uses music it’s never in the wrong way.”

Dr T and the Women (2000)

It’s funny. I don’t think it’s a great film, but it’s so interesting to see someone who is so open to things and who enjoys them. For me it doesn’t mean it’s a good film, but I really like that Jean-Marie doesn’t say, “I’ve seen the Dreyer again at the Cinemateque,” and this is what people think he’s like. It’s not, “I have to see Ordet 100 times”; no, he likes to see Richard Gere.

There seems to be a consensus that Austrian cinema is having a moment. Do you go along with that?

The thing is I’m in a kind of constant fight with Austrian cinema. It’s always so when something is close to you. For me, often what’s regarded as Austrian cinema is something that has a lot of clichéd things in it. They have followed a certain kind of genre – like Michael, which is too easy. I don’t think Austrian cinema is as strong as it’s regarded at festivals. There are some films and some things that are interesting; but often I can smell the concept behind it – one of festivals and art film – too much, and something that is too easy.

How about current British cinema? Marco Müller, the director of the Venice Film Festival, said he thought it was interesting right now.

I did like Wuthering Heights by Andrea Arnold, although many people didn’t. It has its weaknesses, but there’s something very physical in the film. She has a little bit of a problem with the atmosphere and the landscape – it’s a little bit too forced for me – but there are some things I like.

I didn’t like We Need to Talk about Kevin. It doesn’t work; it’s too much. It should have been with the left hand [sic].

Shame I hate. I think the guy is a complete fake. Hunger was a fake too. In Shame everything is there: it’s perfect, every camera movement, every light. And Fassbender is good, but the film is a peep show. I didn’t want it in the festival. Films like this I don’t show, and this is something people criticise me for. Maybe I should let the audience decide, be more open.

India, Matri Bhumi (1058)

I also like the strong link between the Viennale and the Vienna Film Museum, which always has a big programme of films overlapping with the festival.

This has always been the idea, to work on the one hand with the film museum, and on the other with the national film archive. Both collaborations are important, and they work. This is what I’d call a luxury. I don’t take it for granted – I take nothing for granted. This is the connection with history: the old and the new should be connected.

We had 750 people on a Saturday afternoon for the Rossellini film India, Matri Bhumi – it was incredible. This is something I often miss at other festivals. Sometimes I see new films for two or three days, then really wish I could see at least just one film that was made 25 years ago. After all, what are we but history?