1. Aller retour New York

Joseph Strick’s father bought a copy of Ulysses in Paris in 1929. The book was banned in the States at the time, but Strick remembers that during his childhood in Philadelphia, “it was around the house as a holy cultural artefact. People would come over and argue about it, not having read it. My father was a controversialist.”

Ten years later, aged 16, he picked it up himself. “It’s written like a movie,” he felt immediately. “I still maintain it’s a screenplay.” Today Ulysses is an uncontroversial and incontrovertible constituent of the literary canon, and there are dozens of essays and books on its debt to the cinema, many of them jumping off from Joyce’s meeting with Eisenstein, also in Paris in 1929; but 70 years ago Strick’s idea was a relatively esoteric one – particularly coming from a high-school student. He had, however, found one of the few places it might get a hearing. Strick like everyone else had been weaned on westerns and silent comedies, but in the late 1930s, “as I got more and more interested, I’d go up to New York, to the Museum of Modern Art.”

Run by Birmingham-born Iris Barry, MOMA’s film library, founded in 1935, was “really my film school,” says Strick. Barry wrote of the library’s early years that “almost all the films of historical or aesthetic importance were then invisible and in danger of being ultimately lost or destroyed.” Her choices as an archivist and curator still shape our sense of the film canon today, though she herself knew how contingent the whole exercise was. “In gathering together important but long unseen films of the past the Film Library staff, somewhat like Whistler, has had to rely ‘on the experience of a lifetime’.” By 1941 MOMA was able to mount a rolling programme of 300 films through which “day by day the assiduous Museum visitor can follow, over a period of many months, the birth and development of a new medium of expression.” “There were two advantages,” says Strick. “You saw these great movies and there were girls – bright girls from the universities.”

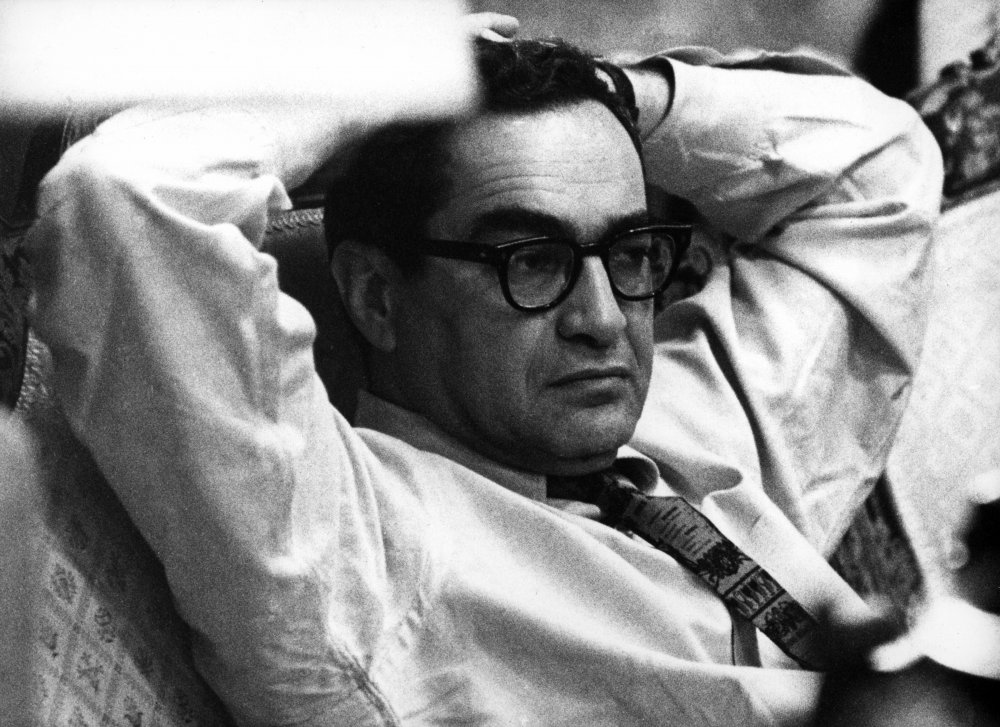

Joseph Strick

A Joseph Strick retrospective ran at the Barbican 19-24 November 2009.

Barry’s sense of crisis was not unrelated to wider events. She had toured Europe collecting prints of the silent classics, as if in anticipation of the coming conflagration, and there was a feeling abroad that the art-form had lost its way since the rise of the dictators and the coming of sound. In 1938 Dwight Macdonald, one of the Trotskyist critics at the Partisan Review, looked back on the first arrival of Eisenstein’s films ten years earlier, when its audience was “a congregation of avant-garde illuminati” and many, Macdonald included, felt the cinema “was the great modern art.”

Stalinism and ‘socialist realism’, he felt, had changed all that. In the same year Henry Miller described Buñuel’s L’Age d’or as the last of the French avant-garde; after it “there remains only the mass production of Hollywood.” New York was a refuge not just for films but for scores of displaced artists and intellectuals. When I tell Strick that Barry had been involved in the physical production of the Egoist edition of Ulysses in 1922, he asks, “and whom did she hire as an assistant? Buñuel.”

Strick had also fallen in with a group of left-wing film-makers through a youth theatre company with connections in New York, among them Ben Maddow, Irving Lerner, and Sidney Meyers. These men, slightly older than Strick and profoundly shaped by the Depression, were perennially involved in savage and sectarian debates over politics and aesthetics. Their motto at the film collective Nykino was that “there can be no effective propaganda without good art.” As it was for Macdonald, Soviet montage of the 1920s was their aesthetic lodestar. “It was a kind of brotherhood,” says Strick of their milieu. Not cut out to be an ideologue, Maddow had gone into film as a poet, writing in 1936 on the ‘cine-poem’. “One sees, hears so much that known forms of art cannot contain. Perhaps into the method of the cine-poem, we have a medium which can encompass modern events their violent compressions and simultaneities.”

2. Bottle-glass and sellotape: Muscle Beach

In 1941 Strick went to study physics at UCLA, on the grounds that “that’s where movies were made,” but his route into film was more circuitous than anticipated. College was soon interrupted by war and Strick signed up, taking part in the campaign against the U-boats off the Atlantic coast as an aerial photographer. “I had access to all this fantastic machinery – 16mm gunsight cameras, all you wanted – and a laboratory right there ready to process it. So you had to make films, right?” Slapstick comedy predominated. After demobilization he returned to LA. “I went to see Ben Maddow, and I said, ‘How do you become a movie director?’” Maddow, who like many veterans of the left-wing film units of the ’30s, had served in the Office of War Information, and was now plying his trade as a screenwriter, suggested nothing so conventional for his young friend. “He said, ‘Well, you’ve got to learn what is visually extraordinary. You’ve got to get a camera and go out and shoot.’” This wasn’t the likeliest way to get into the pictures in the mid-1940s, but Strick heeded his advice.

Shirley Clarke, director of The Connection (1961), once claimed that the post-war resurgence of the American film avant-garde owed its existence to the glut of film-making technology produced for the war effort and going cheap afterwards, and Strick fits the pattern. Working by day at the Los Angeles Times, he obtained a war-surplus bombsight camera with a ‘bottle-glass’ lens, and “rigged up a viewfinder with sellotape and paperclips.” With Lerner he made Muscle Beach, a lightly satirical short about a then-new Californian subculture – bodybuilding as a spectator sport – that was selected by Cannes in 1949. Though unseen by the jury, says Strick, the film caught the eye of the young British critics Lindsay Anderson and Gavin Lambert. “’At last somebody has had the courage to frame things off-centre,’” he quotes them, chuckling in recollection of his DIY camera. “That’s how I learned about film criticism.” (Anderson’s Free Cinema contribution O Dreamland, made in 1953, closely resembles Muscle Beach in technique.)

Muscle Beach was a calling-card of sorts, but Strick found himself employed making “dreadful movies”, “real trash”. In particular? “I hate to tell you. I decided that it didn’t matter if I made that kind of movie: somebody else would make it.” He diversified, becoming a successful entrepreneur selling scientific equipment, and was soon able not to depend on hackwork, though he still had movies in mind. “I went back to Ben Maddow and said ‘what do we do now?’” Maddow was at a similar impasse. Having become a highly respected screenwriter, notably with John Huston on The Asphalt Jungle (1950), he had soon fallen victim to the blacklist. Though he kept writing – possible credits include Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar (1953) – Maddow’s work was strictly anonymous. He saw himself and the other East Coast intellectuals in Hollywood as “transplanted, in alien territory.”

3. The air-conditioned nightmare: The Savage Eye

The Savage Eye (1959)

Maddow and Strick’s original conception for what became The Savage Eye was “Los Angeles as it would be seen by Hogarth.” But as Strick went out filming, using a wind-up Eyemo, this idea – and similar, such as “Dante and Virgil in the Seventh Circle of Hell in Los Angeles” – began to feel arty and didactic. Shooting continued even while the script was being written, gathering together an impressive spread of collaborators over the years of evening-and-weekend production. “The thing about Hollywood is that people are so overpaid that if you have something that interests them, they’ll work for nothing.” As well as Maddow, Lerner, and Meyers, Strick’s colleagues included Helen Levitt, who as a photographer in New York had developed a right-angle viewfinder in order to catch people unawares, and who had made in the 1940s – also using surplus military gear – the landmark documentary In The Street. He also brought on board some younger, untested talent.

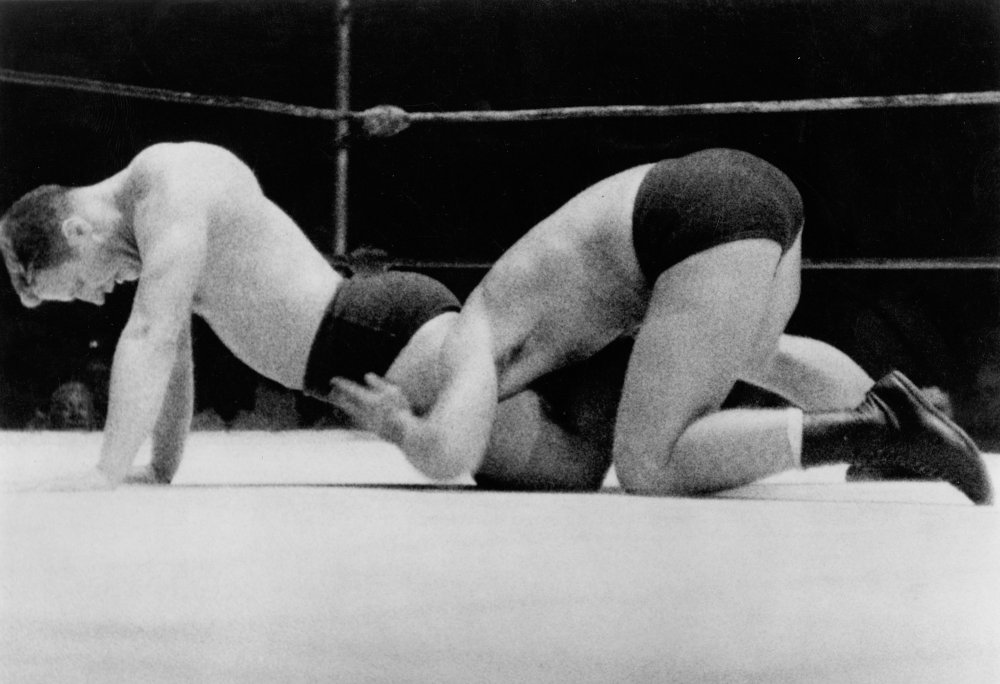

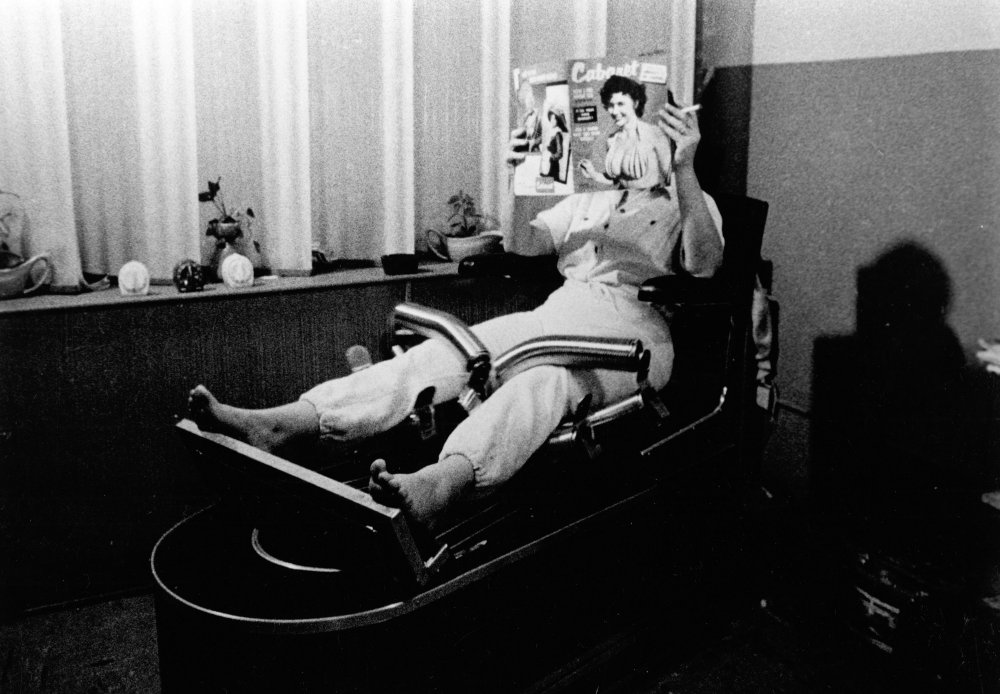

Strick knew Haskell Wexler, then starting out as a cameraman, through his UCLA contemporary Barney Rosset, legendary proprietor of Grove Press. “Joe Strick would call on Thursday and say that on Friday we were going out to the wrestling matches,” Wexler recalled. “It was very badly planned,” but “a good time, better in some ways than being ‘successful’.” Strick describes his technique as being based on the special alchemy of creative components on the day. “You don’t decide on anything till everybody’s on the set, or on the location. You see the elements develop, and you develop them.” Sight and Sound’s Gavin Lambert, who had escaped the editor’s chair for Hollywood in 1956, also tagged along. Strick puts on a plummy accent, recalling the scene – an evening at the wrestling “was not exactly [Lambert’s] style.” The amassed footage documented what Henry Miller – last of the expatriates, first of the beats – called on his return to the US the “air-conditioned nightmare”.

The Savage Eye (1959)

Eventually Maddow and Strick landed on the framing device of a woman spending a year in LA while her divorce is being processed; her unhappiness, expressed in voiceover duel that pits her against a male tormentor-cum-interviewer-cum-conscience, helps explain – a little awkwardly – the film’s excessive dyspepsia. (“These are your deities,” she says of a group of shoppers, over shots of mannequins.) As Strick admits today, “actually, the movie was about our vision of Los Angeles – it was a slight cover-up.” It was also a way of getting away from what Strick regards as the dead hand of documentary, the voiceover that “tells you what to think.” Though Judith X, The Savage Eye’s divorcee, is the anti-Molly, her affairs not just loveless but joyless, there is nonetheless an obvious connection with the Ulysses film Strick had by then had in mind for nearly two decades. When I put it to him that the film was a kind of dry-run, he concurs. “At the time I never thought I’d get it – I didn’t even know if I’d ever finish the feature.”

The Savage Eye finally appeared in Europe in the autumn of 1959, shortly after the nouvelle vague broke over Cannes. On its Edinburgh festival debut the art critic David Sylvester, moonlighting at the movies for the New Statesman, called its vérité visions of LA “sharp, intense, spectacular, and imaginative”, while the veteran documentarist Paul Rotha hailed a film that “exploits the concealed candid-camera in a more revealing and devastating way than ever before.” It made its public debut in London 50 years ago, on almost the same day that Cassavetes’s Shadows opened in New York, and played at the Curzon for almost three months. “Possibly it will provoke more argument than any film since Citizen Kane,” wrote the Observer’s Caroline Lejeune. The Savage Eye went on to be lumped together – with Shadows, The Connection, and the collaborative beat effort Pull My Daisy - as a putative American New Wave. Dwight Macdonald, by now an ex-Trotskyist, was among the more prominent critics who viewed it, in his balefully influential diatribe ‘Masscult and Midcult’, as part of a redemptive ‘off-Hollywood’ movement, a sign of hope in the wilderness.

4. Scaling up: The Balcony

Like most creative people, Strick does not want to be thought of as part of any kind of movement. “All that interests us is the work.” Moreover, he notes, American independent cinema long predated the turn of the 1960s, naming with particular warmth Meyers and Levitt’s The Quiet One (1948), a semi-documentary feature that was nominated for an Oscar. There is in any case little stylistic common ground between Strick and Cassavetes. “John didn’t know how to frame a shot – he was an actor. It’s not in his purview.” Instead of parlaying his success into a Hollywood contract, as Cassavetes did initially, Strick set out to adapt Jean Genet’s The Balcony outside the system. Largely set in a brothel, Genet’s play, with its presentation of political power relationships as merely performative and rooted in sado-masochistic fantasy, could not have been made any other way, and was largely financed by Walter Reade, Jr, a theatre chain-owner who had been distributing art-house fare in the US since the mid-1950s.

Strick was on the board of Grove Press, infamous in these years for a series of victories over censorship – it published Henry Miller and William Burroughs – and was able to work with Genet (another Grove author) directly, selling him on the idea, realised in the film as shot, that “film studios are whorehouses.” In 1964, the year after the film’s release, Strick contributed – with Godard, Kubrick, and Losey among other luminaries – to a Sight and Sound questionnaire on “the question of independence,” discussing three types of cinema. “Subsistence film-making” was how he characterised the after-hours work that produced The Savage Eye; The Balcony, meanwhile, was “scale level”, using small crews and casts – in this case including Shelley Winters, Peter Falk, and Leonard Nimoy – who were prepared to defer payments. He proposed never to work in the last category, “industrial,” with all the loss of control that implied.

5. A day in the life: Ulysses

Ulysses (1967)

It is a commonplace to see the concurrent new waves and underground movements of the early 1960s as the return or revenge of movie modernism, three decades after the eclipse described by Miller and Macdonald. Schematic and misleading though this analysis is, it does capture something of how the moment was perceived at the time. Not only were these the years of Resnais’s and Antonioni’s boldest works, and of Buñuel’s return to Europe, but the modernist literary canon had also begun to reach the screen, a phenomenon epitomised by Orson Welles’s The Trial. Even Hollywood wanted a piece. In 1960 Jack Cardiff had directed a version of D.H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers, co-scripted by Gavin Lambert, for Fox, and its producer Jerry Wald was threatening to make the logical next step and film Ulysses, easily outbidding Strick for the rights. But Wald, says Strick, was consumed by the need to produce a sequel to Peyton Place, and when he died in 1962 Strick had a second chance.

Strick’s struggles to obtain the rights without studio support, and his subsequent battles to secure financing, were protracted, but finally in mid-1966, having won Reade’s support to produce the film through British Lion, a consortium of producers “at war with each other”, Strick started filming on the streets of Dublin. He wanted – still wants – to film the whole 18 hours that the book encompasses. (“Gimme the money, man, I’ll show ya.”) Perhaps it was Strick’s exposure to the book in adolescence – and outside the schoolroom or lecture-hall to boot – that gave him the confidence to cut through the thickets of potential misgivings and put on screen what he called at the time “the intellectual’s declaration about sex, about nationalism, about religion – about everything.” More than practically any other book, Ulysses guaranteed opprobrium for its adaptor, and on its arrival the Monthly Film Bulletin complained that Strick had retained the sex-talk and lost the classical references, making the knockout observation that “it is not Joyce’s novel.” By the 1960s, if not before, the latter had become the possession of a jealous critical cult.

On Ulysses first publication, however, the great critic Edmund Wilson, though he greeted it as “a work of high genius”, nonetheless found Joyce’s terminal allusiveness a bore, and saw no problem in saying so, advocating drastic cutting. “When he insists upon describing a drinking party in an interminable series of imitations which progresses through English prose from the style of the Anglo-Saxon chronicles to that of Carlyle,” wrote Wilson in the New Republic, “one begins to feel uncomfortable.” Strick today maintains that the classical references are inessential. (Or, as Henry Miller, no Joyce fan he, put it in Tropic of Cancer, later adapted by Strick, “every man with a bellyful of the classics is an enemy to the human race.”) What matters far more is his conjuring up of a rich internal reality for the characters.

Ulysses (1967)

It is perhaps the spectre of Eisenstein that haunts any potential metteur en scène, owing to the glamour of his and Joyce’s shared epoch. Their fabled meeting has inspired a kind of modernist slash fiction, but Joyce’s reported comment afterwards that Eisenstein or Walter Ruttmann would be his preferred adaptors has to be weighed against the fact that he had never seen a film by the former, and that the latter can only have been picked because his most famous film, Berlin: Symphony of a Big City (1927), was a day-spanning ‘city symphony’ which had some superficial structural congruity with Joyce’s novel. Neither director, Ruttmann in particular, was a strong candidate for handling its more tender and comic parts, and Eisenstein’s writings reveal that he responded to Joyce’s technical experiments only as such. His comments on Molly’s monologue are cold and slip into cod-Marxist verbiage (“Joyce has caught one of the deep layers of the primary stage of consciousness development…”).

Rather, Strick considers Buñuel – whose work Eisenstein thought “unhealthy” – the most Joycean of directors. His own film was almost obscured by the two secondary arguments that met its unveiling in 1967 – one over adaptation, and the other over censorship – but it played at the Academy, then London’s main art-house cinema, for 16 months, spending most of that time on the main screen. Released on 1 June, the day Sergeant Pepper appeared, it was still running in May 1968 and beyond. Molly’s monologue, the source of most of the controversy at the time, occupies almost a quarter of the film, and finds Strick at his most Buñuelian, though Belle de Jour (1967), the film this passage most resembles, was in fact its exact contemporary. Brilliantly performed by Barbara Jefford, the voiceover was recorded prior to shooting, but the aim was not simply to illustrate it. “You mustn’t show them what’s being said – that’s square.”

Strick had managed to attract to the film Reggie Mills, who had edited extraordinary runs of films for both Powell and Pressburger (A Matter of Life and Death, Black Narcissus, The Red Shoes) and Joseph Losey, and the long montage sequence that accompanies Molly is a tour de force. Mills “added something to the picture,” says Strick, describing a quick-cut counterpoint to Molly’s fantasy about picking up a sailor. Joycean scholar Margot Norris, in her excellent and appreciative book on the film, writes that “the film’s fantasies of Molly in bed with the professorial Stephen, reading with the absurd spectacles that turn even a chaste kiss into a poke in his eye, offer a cinematic invention that shows Molly is a different woman for different men.” It doesn’t exactly diminish the film to say it sends you back to the book, in my own case a prospect made off-putting principally by the quantity of bad commentary it has inspired. I had forgotten that Ulysses could be moving.

Given its sheer fecundity as a source, it is surely surprising – rights issues to one side – that so few have followed Strick’s lead in adapting it. He is quite modest about the result – “I think it succeeds every now and again” – and is clear that his is not the only possible Ulysses. As a practitioner of “subsistence filmmaking” some five decades before digital video and the internet made the notion fashionable again, he seems to be throwing down the gauntlet.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.