Web exclusive

What the censor saw: Violated Letters (2011)

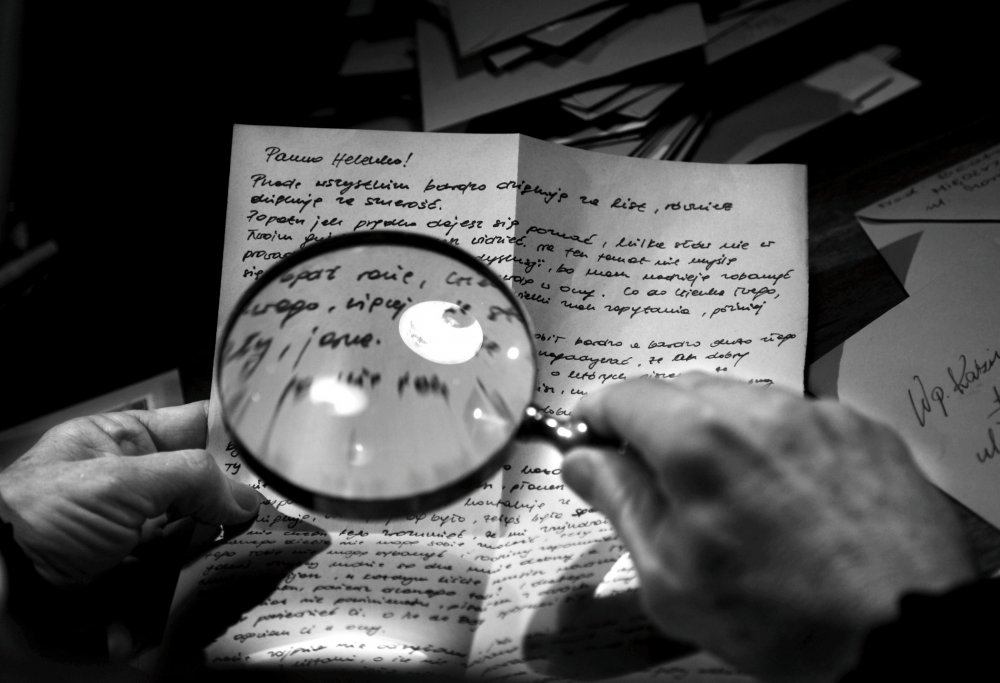

The archive under communism was a bottomless arsenal of information. Obsessive surveillance produced endless anthologies of mundane data, ever-growing bunkers of papers, files, photographs and films; knowledge-ammo gathered against that enemy of the paranoid state, its own public.

In his new film Violated Letters (Cudze Listy, 2011), Polish filmmaker Maciej Drygas reopens these archives with the forensic eye and patience of an archaeologist, revealing piece by piece the bones of a huge infrastructure of distrust lain dormant beneath Polish society for two decades.

The film reveals the frantic activities of Poland’s post censors, who intercepted tens of millions of letters annually, in massive violation of the constitutional right to privacy. Private letters seized by the secret service – bitter jokes to friends, worried nagging from distant mothers, pleas from children to the citizen president – are read out alongside archive footage (from a range of Polish repositories) of youth parades, hospital maternity units and workers eating their lunch, all evidence of the everyday in socialist Poland between the 1950s and 1989. The tone hovers between the observational and the invasive, suggestive of the fine line between observational creativity and surveillance. The sum effect is to insinuate the private temper of a population, a collective unconscious, while also revealing a government so insecure it treated even the most banal of complaints as treason.

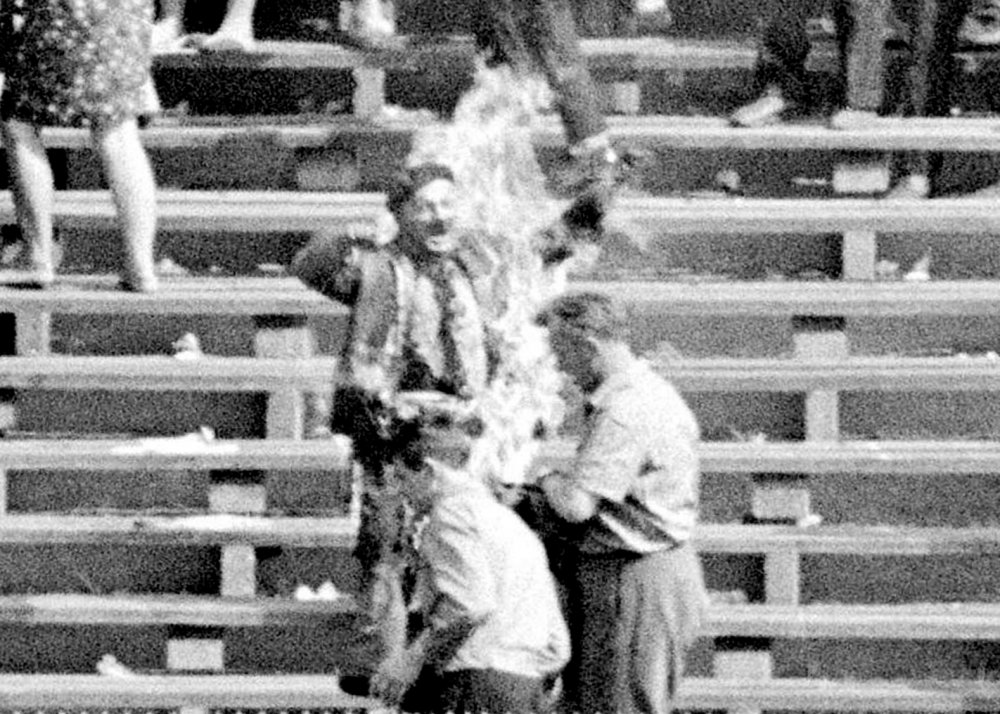

From his debut Hear My Cry (1991) onwards, Drygas has found a filmic home amongst the archive (perhaps surprisingly for a man allergic to dust); he’s learned to allow its footage to speak for itself. With each film he’s moved further away from well-worn documentary formats – talking heads, voiceovers – instead allowing his findings to illustrate for themselves the realities of Polish life under socialism. Counterpointing contemporary interviews with seven seconds of archival material depicting a man burning alive amid a sea of people at Warsaw’s Stadion Dziesięciolecia in 1968, Hear My Cry illustrates the malleability of collective memory, and reveals a formal symmetry with the cinematic itself.

Hear My Cry (1991)

Through a process of watchings, rememberings, misrememberings and forgettings, Drygas reminds us that memory, like film, is collectively directed and re-directed. In his interviews with witnesses of Andrzej Siwiec’s self-immolation protest, the most shocking revelation is the public’s overwhelming indifference to it. One woman describes his death: “He yelled a lot, but the music obscured his cries” – the somewhat horrid irony being that his protest was swamped by Harvest Day songs, in all their quaint Polish conservatism. Yet Drygas does not condemn this indifference, but uses the testimony to reconstruct the now forgotten, mystified or renounced consciousness of 1968 Poland.

At the end of the film, he slows down and loops the footage of Siwiec’s burning body. As he zooms in on his frantic, burning face, each repetition sees the low-grade footage further disintegrate, as if melting itself. This final act shares a cinematic defiance with Harun Farocki’s 1969 Inextinguishable Fire (a protest at the Vietnam War which features the filmmaker’s own act of self-immolation, sustained through an unedited sequence of film) or indeed James Benning’s Milwaukee/Duisburg (2010), in which a 17-second shot of men leaving a Milwaukee factory (taken from Benning’s own 1972 Time and a Half) is slowed down 133 times to become an achingly slow dirge to industry. Through their unblinking slowness, these images force themselves upon one as inscriptions of memory.

In his next film, State of Weightlessness (Stan Nieważkośći, 1994), Drygas continued his descent into the archive, again uncovering a shocking indifference to human life, this time in the context of Soviet space exploration. The film shifts from the transcendental sublime – images from space of our luminous earth, narrated by the recorded voices of the orbiting cosmonauts – to images of the medical experiments inflicted on humans and animals in preparation for this great leap into the universe’s unknown. The film suggests the weightlessness of space as a state of exception, where the quests of science and its then-holy grail of space travel allowed for a deferral of the notional values of humanity.

State of Weightlessness also prefigures many of the themes of Drygas’s later films, as if turning his interest to space provided him with a sixth sense to the ethereal routes of communication that emanate from earth, that act as evidence, perhaps even a tectonic architecture of the desires and fears of recent history. From space, Drygas opens his ears to the battles fought in the atmosphere. Voice of Hope (Głos Nadziei, 2001), for example, documents the wheezing war between the Polish wing of Free Radio Europe and the communist-employed jammers.

Drygas shooting State of Weightlessness (1994)

Interviews with jammers and images from the radio archives document important events in the fight for freedom, from the 1956 Budapest Uprising to the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia. The film demonstrates a never-ending politics of frequency – the air as the frontline in the war for freedom, a space of threat to the communist powers for its ability to contaminate radical ideas, a placeless space where the voice of opposition can disrupt, infect and radiate hope. The battle to control the transmission of the voice, whether written or heard, runs to the core of the socialist surveillance machine.

In One Day in People’s Poland (Jeden dzień w PRL, 2005), Drygas picked an uninteresting day, free of news or scandal, to demythologise Polish socialism. The weather reports predicted scattered clouds, and Warsaw’s newspapers carried stories of low-quality coffee on their front pages, but through scouring security service archives, Drygas reveals an almost hour-by-hour account of the day, pointing once again to the absurdist machine that rumbled beneath this banality. It’s a decidedly grey day-in-the-life, yet it re-establishes the dichotomy that all of Drygas’s films address: the distinction between ‘permitted’ public life and the life of a citizenry in private, a distinction that still resonates profoundly within contemporary society.

It’s this central concern, running throughout his films, that distinguishes Drygas from his predecessors in the world of Polish documentary. For one, he wasn’t educated at the famous Łódź film school under Jerzy Bossak or Kazimierz Karabasz, nor were his films subjected to the strict censorship enforced until 1989. His film education at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography in Moscow – what Drygas calls “the salon of the rejected” [from Łódź] – granted him an inside perspective of communism, what he describes as a better sense of the mentality of its inhabitants.

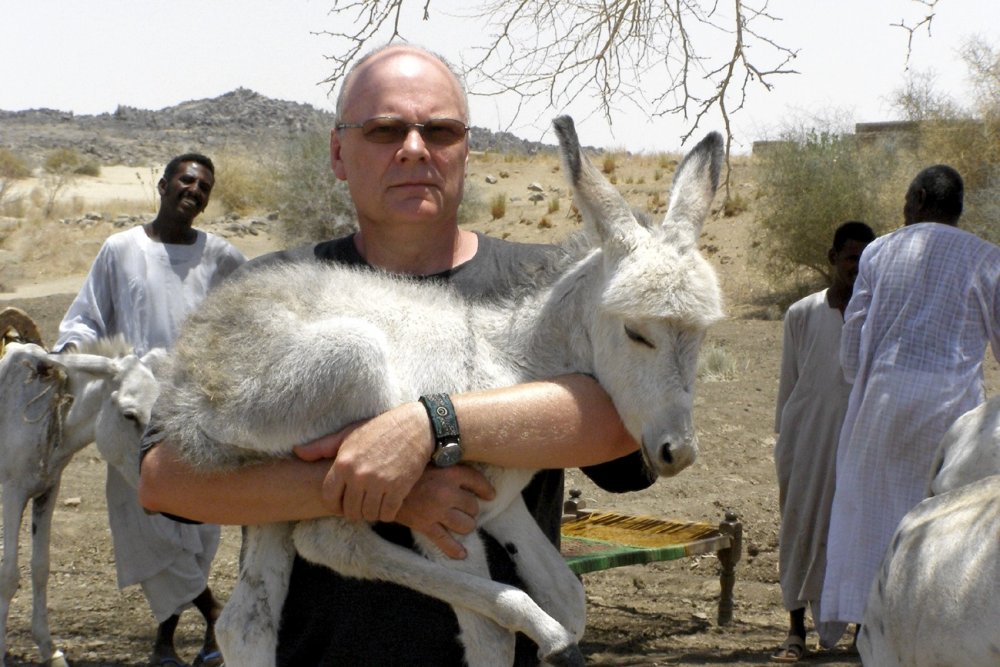

Drygas on location in Sudan for Hear Us All (2009)

Although his films inevitably share strong thematic links with Krzysztof Kieślowski and Marcel Łoziński, the difference in time and place necessitate a different cinematic strategy. As the film-critical Andrzej Werner suggests, “A different set of tactics is used against a living opponent who still holds power, and against the loser, who is not fully defeated in a society itself.”

Informed by his experience in Russia, Drygas clearly developed a profound sensitivity and trust in the poetics of the archive as a means of unearthing the mentality he experienced, of a public unconscious buried and obscured by censors and propaganda. As Violated Letters shows, he is still assured that the vast troves of information collected until 1989 “serve an important purpose… they tell our story at the most fundamental, human level.”

To reach these stories, Drygas plays with archival temporality, reworking and editing images and sounds together until they grant him a new kind of intimacy into the public unconscious they document. It’s an access into a time past through the evidence of its passing – letters, images, recordings held by the state become raw materials for historical fictions, suggestive of collective history, mood, memory, fiction and their necessary confusion.