Tony Conrad, who passed away on 9 April, was a dynamic, exploratory experimental filmmaker and musician, and a vital part of the New York art scene from the early 1960s onward. As Jonas Mekas puts it:

“[Jack Smith’s] FLAMING CREATURES, it wouldn’t even had taken off, if not for the sound track he did for it. THE FLICKER – a monumental work, he seldom even mentioned it, like it was somebody else who made it…Velvet Underground… Would it have happened without him? He never took any credit for it…”

His films were nonfigurative and specific in shape and concept, driven by an interest in perception, human response and the live situation. He introduced and discussed them with great energetic warmth. It was impossible not to be charmed and compelled by this very out-of-the-ordinary individual, who wore a uniform outfit of pure lime green when I last saw him on stage.

The Flicker (1966) presented just black-and-white frames at alternating intervals, flickering at increasing speeds and almost inducing visual hallucinations at its most intense. He mapped out the film on a grid chart which he then used to rigorously construct the 16mm work.

The Flicker (1966)

Conrad had a Harvard degree in mathematics and was influenced by John Cage; both interests came to bear. The film highlighted the mechanical nature of the film projector – light was either allowed to pass by a clear/‘white’ frame or blocked by black leader – and yet its effects depended very much on the individual watching. It opens with a warming that the film may cause epilepsy (though there has been no recorded instances of this occurring). The warning was handwritten and the title card highly decorative and partially abstract, both standing in sharp contrast to the minimalist qualities of the rest of the work (and remaining strangely memorable – at least for this viewer). They suggest that their maker was complex, had character and was at some level interested in aesthetics and expectation as well as pure phenomena. I was very curious about Tony, even before I really knew anything about him.

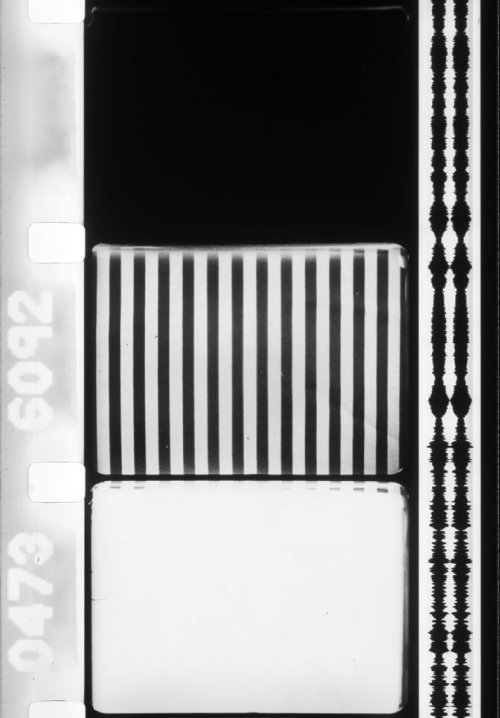

Straight and Narrow (1970)

The stroboscopic Straight and Narrow (1970), made with Beverly Conrad, also explored vision and perception, vertical lines moving intensely in front of the confused viewer’s eyes, apparently introducing colour effects despite being made in black and white. His work was exploratory and yet playful – and extremely inventive, in many cases emphasising extreme physicality in the filmmaking and projection processes. For Film Feedback (1974) he filmed a candle then, after processing and fixing the image in one continuous motion, projected the new sequence back into the location where the candle was still burning, image and source flickering side-by-side. It was like time travel and deliberately mimicked video feedback. For Curried 7302 (1973) Tony cooked film in curry sauce and projected it, the food splattering the internal mechanisms of the machine as the work rattled through, producing bold, painterly, non-representational imagery.

His sculptural approach to filmmaking extended to music and he would literally bow strips of taut 16mm film. He also took an interest in duration, and initially with La Monte Young and John Cale he played sustained drone music, playing for hours at a time, bowing a violin connected to a microphone pickup and creating a sound akin to a jet-plane taking off. Those early sessions were extremely important to the development of the Velvet Underground, and Tony continued to play regularly in this manner, performing with Faust, and in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern as recently as 2008, a show that incorporated shadow play and all manner of different objects. I met him briefly in Norwich when he gave me a new print of The Flicker to pass on to his UK distributor LUX. Tony maintained good, close contacts with the UK and anyone who knew him or saw him speak will miss both the man and his distinctly live presentations very much indeed.

— William Fowler, Curator of Artists’ Moving Image, BFI National Archive

Filmmaker William Raban adds…

I first met Tony in 1971, or was it 1972, when he was staying with his wife Beverly at Malcolm Le Grice’s home in Harrow. I saw another side of Tony when I visited SUNY at Buffalo in 1976. There he was clearly an inspiration to his students, working alongside such luminaries as Paul Sharits and Hollis Frampton. We met many times since then, mostly at film screenings, and if Tony was in the programme you knew it was going to be fun whether he was screening The Flicker, pickling film or playing the 16mm-film strip using the bow of his violin. I later marvelled to discover that he played with such greats as La Monte Young, John Cale and Lou Reed, and is credited with giving the name to the Velvet Underground.

For an artist with such a distinguished career in music and film, this photograph exemplifies Tony’s charming modesty. He is the figure behind the statue in a Dortmund Park (2004). Left to right: Willhelm Hein, Anthony McCall, Tony Conrad and William Raban.

Credit: Mark Webber

I shall miss you deeply Tony, you inspired me and countless others and I know your work will continue to inspire generations to come. I hope you will also be remembered for your humility and for your wicked sense of humour and fun.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.