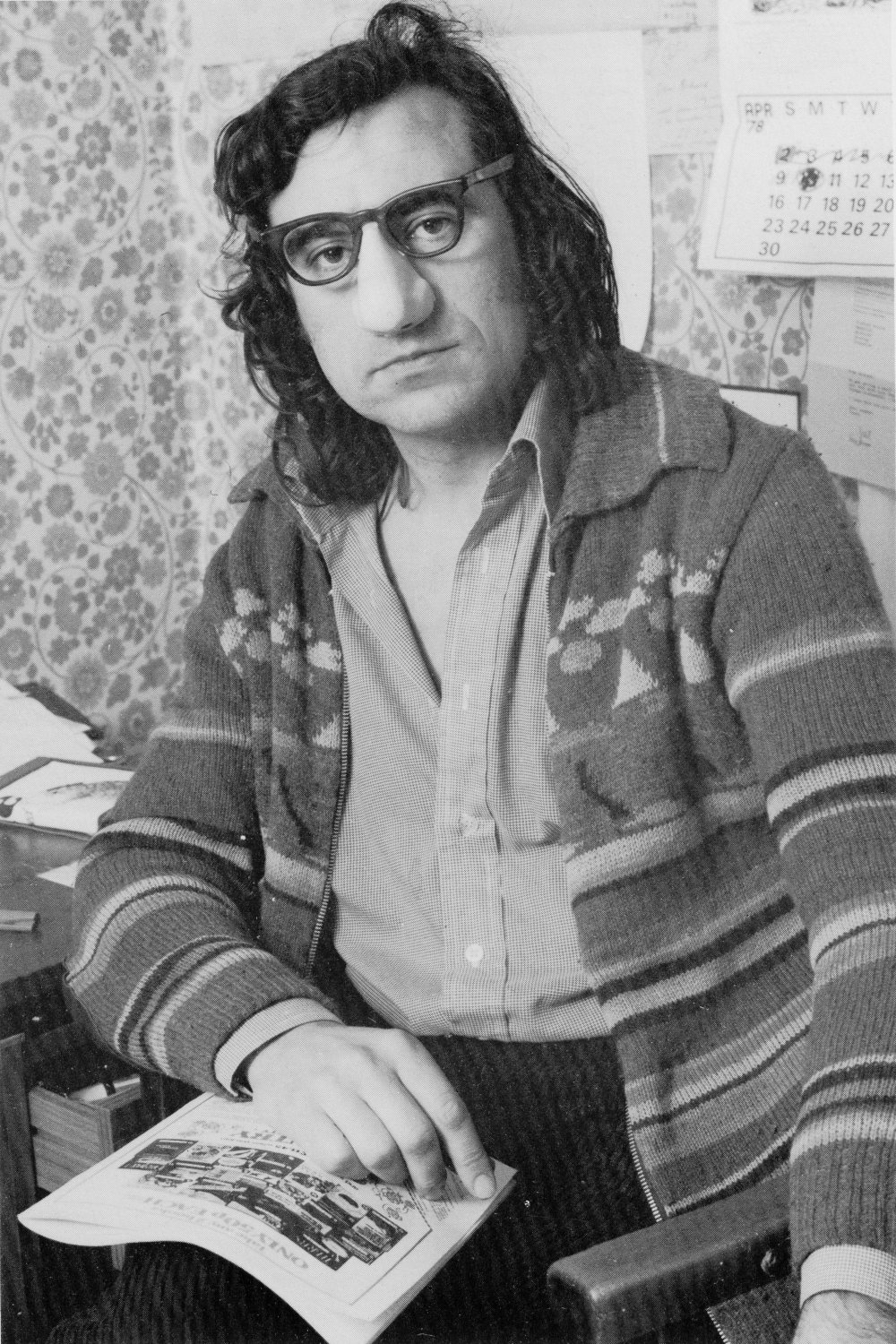

Credit: BFI National Archive

When Clive James died in November 2019, much of the coverage stressed his extraordinary breadth of interests in a way that almost seemed designed to minimise the fact that he was primarily famous in the wider public eye for being funny.

Nobody could sensibly play down that quality in Terry Jones: although he parlayed a passionate interest in medieval history into a wholly serious book (Chaucer’s Knight: Portrait of a Medieval Mercenary, 1980) and an equally passionate disgust with 2000s government warmongering into excoriating newspaper columns, he primarily sought to make viewers and readers laugh until they bust a gut, if hopefully not as graphically as Jones’s notorious Mr Creosote. Although Jones characteristically played this down: “I’d never had any particular interest in comedy. Humour was just something that came with everything as far as my brother and I were concerned. Why should you ban laughter from any aspect of life?”

Born in Colwyn Bay on 1 February 1942, Jones felt so strongly about a deeply unwanted family relocation to Claygate in Surrey that he rarely missed an opportunity to emphasise his Welshness thereafter. (This wasn’t always reciprocated – Life of Brian was banned for years in Swansea and for decades in Aberystwyth.) He read English at Oxford, where he made a lifelong friend and creative partner in Michael Palin, initially as a fellow member of the Oxford Revue comedy troupe.

Parlaying newly-acquired showbiz contacts into television commissions, Jones and Palin contributed to The Frost Report (1966-67) as writers before appearing on camera in Twice a Fortnight (1967), Do Not Adjust Your Set (1967-69), Broaden Your Mind (1968) and The Complete and Utter History of Britain (1969). The latter was ostensibly a perfect Jones creation, presenting historical events as if covered by contemporary television (like Peter Watkins’ Culloden, but with jokes), but dissatisfaction with the final product made him vow to start directing his own material.

Many of these projects also involved Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam and Eric Idle, with whom Jones and Palin created the revolutionary BBC sketch show Monty Python’s Flying Circus (1969-74), with Jones frequently taking the lead in shaping and structuring each instalment, as well as playing countless memorable grotesques (particularly women of indeterminate shape and age). As co-directors of Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), Jones and Gilliam pooled a shared medieval-history obsession, with Jones directing the next two Python features solo: the more pointedly satirical Life of Brian (1979) and the scattershot but still hilarious The Meaning of Life (1983).

Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979)

Had Jones done nothing but that, his place amongst the comedy immortals would still be as solid as a direct hit from a 16-ton weight, but his non-Python output was equally hefty. With Palin (who also starred), he wrote the blissfully funny BBC series Ripping Yarns (1976-79), tales of good old British pluck and gumption set against such backgrounds as a cursed Victorian artefact, the height of the Raj and a failing Yorkshire football team.

Further feature films as director included Personal Services (1987), an underrated take on the Cynthia Payne scandal; the disappointingly sluggish Norse romp Erik the Viking (1989); an affectionate live-action interpretation of The Wind in the Willows (1996); and, sadly, a less than memorable swansong in the sci-fi comedy Absolutely Anything (2015). He also had a solo screenwriting credit on Jim Henson’s fantasy film Labyrinth (1986), despite his initial draft being extensively reworked by others.

Personal Services (1987)

Interspersed with this, he wrote several children’s books and frequently returned to his beloved Middle Ages, realistically in the Emmy-nominated Terry Jones’s Medieval Lives (2004), and fantastically in the animated Blazing Dragons (1996-98), in which dragons are the protagonists and humans the disposable villains. He also wrote poetry, although cheerfully acknowledged that he was no Dylan Thomas, whose radio play Under Milk Wood he first listened to as a child specifically because it was Welsh. He made a late foray into opera with Evil Machines (2008) and The Doctor’s Tale (2011), both co-written with the composer Anne Dudley.

After surviving a mid-2000s cancer scare, in 2015 Jones was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia (FTD), whose impact on his ability to communicate was a particularly cruel blow for someone so jovially garrulous. He doubtless saw himself as more of a naughty boy than a Messiah, to invert one of his most famous lines, but the reaction that followed the lunchtime announcement of his death on 22 January 2020 suggested otherwise, with Palin’s characterisation of him as “the complete Renaissance comedian” smacking less of hyperbole than strongly evidence-backed fact. But as Jones’s iconic naked organist ascends into the heavens, we can console ourselves with what he left behind, and it’s not at all far-fetched to imagine a 27th-century scholar discovering Life of Brian with as much enthusiasm as Jones’s own discovery of his medieval forebears – and many of Chaucer and Boccaccio’s jokes still weather the test of time.

-

The 100 Greatest Films of All Time 2012

In our biggest ever film critics’ poll, the list of best movies ever made has a new top film, ending the 50-year reign of Citizen Kane.

Wednesday 1 August 2012

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.