“I was dead. I was a dead man walking. And I still am a dead man walking. It is extraordinary that I have fiddled along for six years or something and I am still standing on my feet. I have a woman that is 36 years younger than I am. It is insane, the whole thing. But here I am.”

— Paul Cox, September 2015

Born in Venlo in the Netherlands, less than a month before the Nazi invasion of the country, Paulus Henrique Benedictus ‘Paul’ Cox came to Australia on a post-war immigration program in 1963 and two years later settled in Melbourne. That same year he started to make short 8mm and 16mm films (he was already a working photographer), and over the following half a century he became Australia’s most prolific auteur, producing 19 feature films, 13 short films, 12 documentary films and a host of television programs, books, photographic series and artworks before his death this past June.

“I was hooked,” he recently explained to me of his first steps in filmmaking, “but it wasn’t out of choice. I don’t have the nature to walk into a saloon and get my gun and shoot in the air and say ‘Listen to me’. I go about it in a determined but in a very different way.” Indeed, Cox’s determination and difference produced a creative legacy remarkable for much more than mere quantity.

The film that launched him to international fame was Lonely Hearts (1981), a compassionate and, at times, very funny tale about two offbeat characters falling in love. It was followed by Man of Flowers (1983), which premiered at Cannes in 1984 and secured Cox’s place as an idiosyncratic director who adapted European Romanticism to the contemporary Australia screen. While Cox’s reclusive male lead Charles Bremer (a role that won Norman Kaye the Best Actor Award at the Australian Film Institute in 1983) was consequently depicted as an eccentric individual who lived alone, Bremer’s engagement with the arts was filmed in lush colours and in an emotional and expansive way: besides Lisa, the young model who stripped for him to the love duet from Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, Bremer loved music, opera, painting, flowers and collecting decorative art objects.

A shot from Man of Flowers (1983)

The lead characters who populate Cox’s subsequent films keep this focus on the creative, sensitive and often lonely adult man. With a couple obvious exceptions – the exploration of a woman’s failing eyesight in Cactus (1986) and A Woman’s Tale (1991), in which Martha’s experience of terminal cancer mirrored the real life story of Australian actress Sheila Lawrance – Cox’s films explore the emotional and creative life of men. My First Wife (1984), Vincent: The Life and Death of Vincent van Gogh (1987), The Diaries of Vaslav Ninjinsky (2002), and Force of Destiny (2105) operatically amplify experiences that we all share: relationships, illness and death. Particularly in the works that explore the life of individual artists – Vincent, Ninjinsky and Force of Destiny – Cox documents our capacity to care, not just for each other, but for art, creativity, and emotional truth. These are subjects and experiences often overlooked in commercial cinema. A staunch supporter of independent film, Cox explained to me that he wanted authenticity, lived experience and unpretentiousness to inform filmmaking.

“Why not Star Peace?”, he vehemently asked me, echoing a line a character says in his newest film. “Why not Star Peace in the heavens above us?” he went on. “Where is the artistry, the nobility? [Why can’t we make] something beyond the normal human nonsense?”

When I interviewed Cox last year he was clearly still the firebrand I knew and loved. I first met him in February 2009, when I was involved in convening a conference and film programme in his honour at the University of Melbourne (Paul Cox: Miracle Maker). This was the month that Cox had been diagnosed with liver cancer. Elizabeth Presa, a long-time friend and herself a celebrated artist, tasked me to gather a generation of collaborators and friends who had worked with Cox. I felt as though we were programming a living wake, an homage that a generation of Australian sculptors, painters, actors, dancers, sound engineers, poets and filmmakers wanted to pay a fellow artist while he still lived.

The sadness of the event was offset by the substance of what people were saying to me. The 1970s and the 80s in Melbourne were reintroduced as a period of time when artists collaborated across the arts on projects whose focus was human relationships. Cox, I began to realise, was not so much a lone maverick as a beloved member of a community of makers, creators and doers that had long defined (and sometimes even defied) ‘art’ in late twentieth century Australia. Greg Burgess, Asher Bilu, Julia Blake, Paul Carter, John Clarke, James Currie, Paul Grabowsky, Chris Haywood, Rodney Hall, Wendy Hughes, Tony Llewellyn-Jones, Ian Jones, Bruce Myles, Natalie Miller, Maudie Palmer, Elizabeth Presa, Tom Ryan, Delia Silvan, Pip Stokes and David Wenham were among the people who gathered to celebrate Cox and reflect upon the friendship they had built and shared. The article that Roger Ebert wrote for the occasion and that was subsequently published in Senses of Cinema (Ebert was too ill to join us) explained that Cox was, for those who worked with him, “a friend for life”. Ebert concludes: “Paul Cox is a great film director, a great artist, and above all, a great soul.”

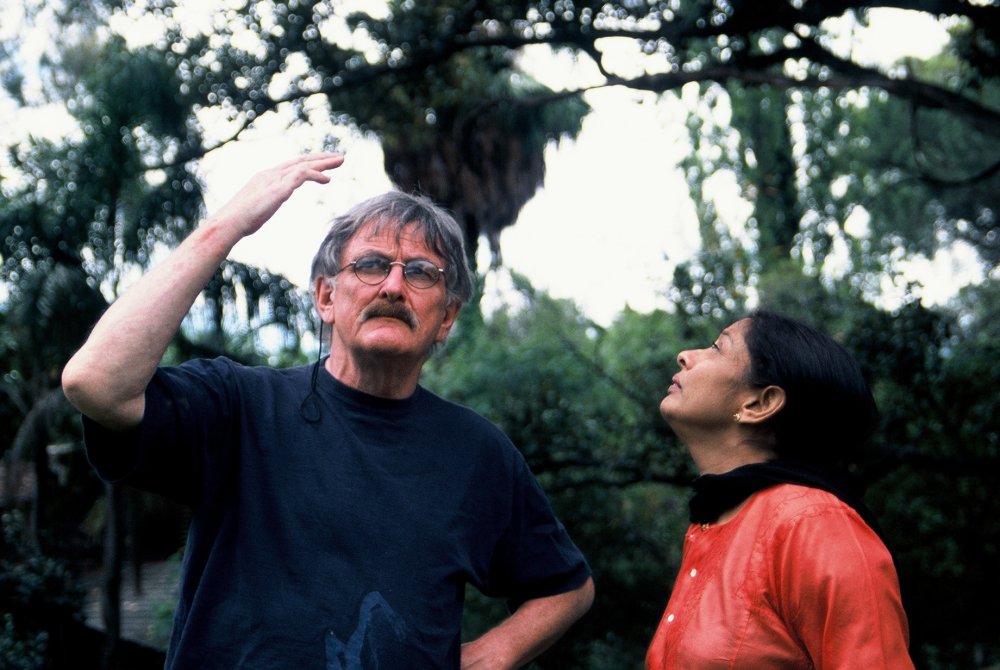

Paul Cox in September 2015

Credit: Victoria Duckett

Few people expected Cox to survive 2009. He was, however, the recipient of a liver transplant on Boxing Day. Over recent years I enjoyed visiting him in his sprawling home that was his creative cocoon in Albert Park, Melbourne. Originally doubling as a film production house (where Cox ran Illumination Films for roughly 40 years), it was packed full of books, files, photographs, mementos and things collected on his extensive travels. Cox enjoyed detailing the provenance of the objects that surrounded him.

Most of all, he enjoyed recounting how he serendipitously came to own the house itself. As he cheerfully explained, in the 1970s he was a poor artist wandering the neighbourhood. Chancing upon the block at an auction, he placed the winning bid. He then had to find a friend to pay the deposit. The gamble paid off: Cox became the owner of a prized piece of real estate, living minutes from the beach.

I have come to see this tale of serendipitous acquisition as a model and metaphor for Paul’s creative life. A tremendous believer in making the most of opportunities, he had a canny ability to repurpose lost, overlooked or unwanted objects. More importantly, he also knew precisely what he wanted. As he explained to me, speaking about the film (Inferno) that he was working on at the time of his death: “If you have your direction worked out, and say ‘That’s where I am going,’ the world is so mad they let you to go there. As long as you are tenacious, you find the world around you suddenly participates in the action.”

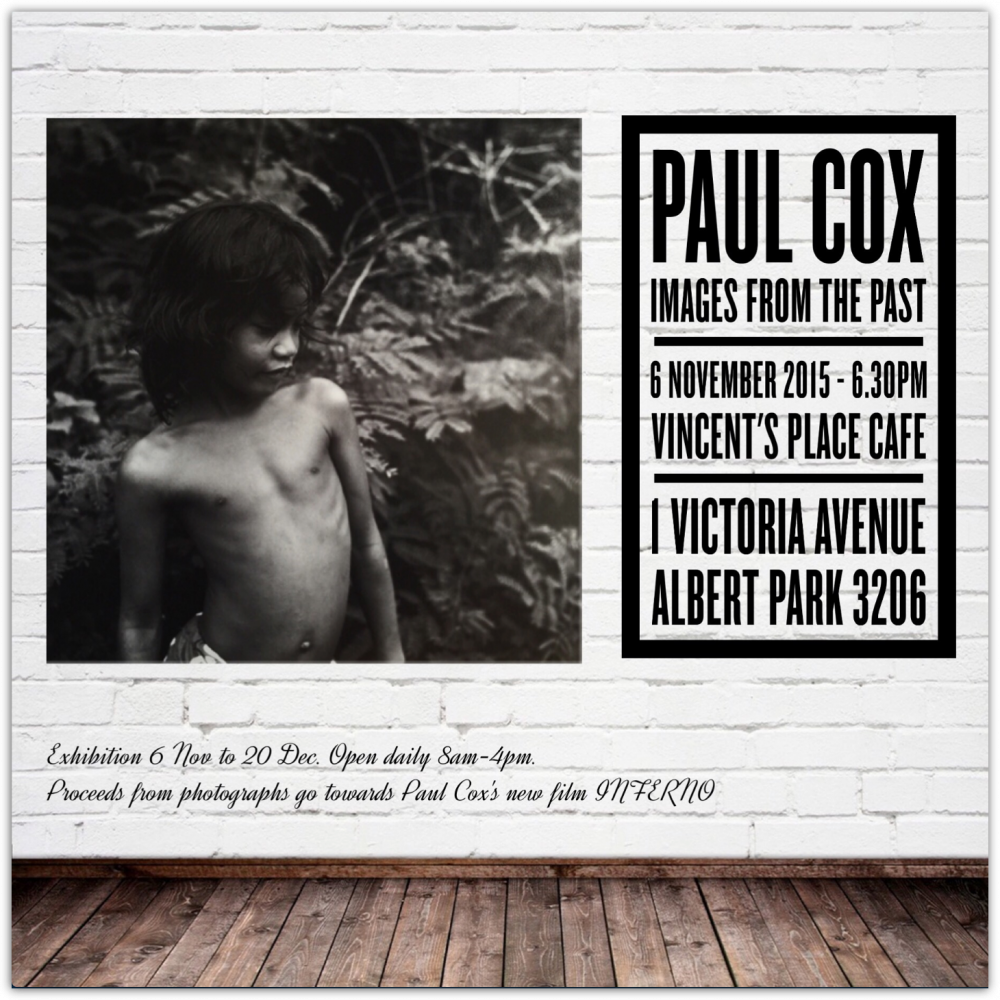

Cox was certainly tenacious. He outlived some of his friends and collaborators (Ebert, Hughes, Stokes, Kaye and, more recently, Bob Ellis). When receiving his liver transplant he met Rosie Raka – a woman who was also a transplant recipient. Together, they repurposed some of his house, founding a hip café called Vincent’s Place (named after fellow Dutchman Vincent van Gogh and the focus of his celebrated 1987 documentary Vincent).

The poster for an exhibition of Paul Cox’s photography at Vincent’s Place in November 2015

Writing a book about his experience of liver cancer (Tales from the Cancer Ward) and making films about being a liver recipient (the aforementioned Force of Destiny as well as the 2012 documentary The Dinner Party), Cox ensured that his illness, his transplant, the ongoing need for organ donors and above all his love for Rosie remained both public and visible. The point he reiterated was not that he was a survivor, but that his own life was made possible by the care and generosity of others. Cox’s legacy is consequently far more than a long list of Australian arthouse films. It is a rally to life, and a belief that the movies can indeed move people, prompting humane action even in “the blindness, the stupidity, the danger, of this very troubling time”.

All quotes, unless otherwise noted, are taken from an interview the author conducted with Paul Cox on 9 September 2015.

The Dinner Party (2012), a 52-minute documentary Paul Cox made about the experiences of organ recipients

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.