Web exclusive

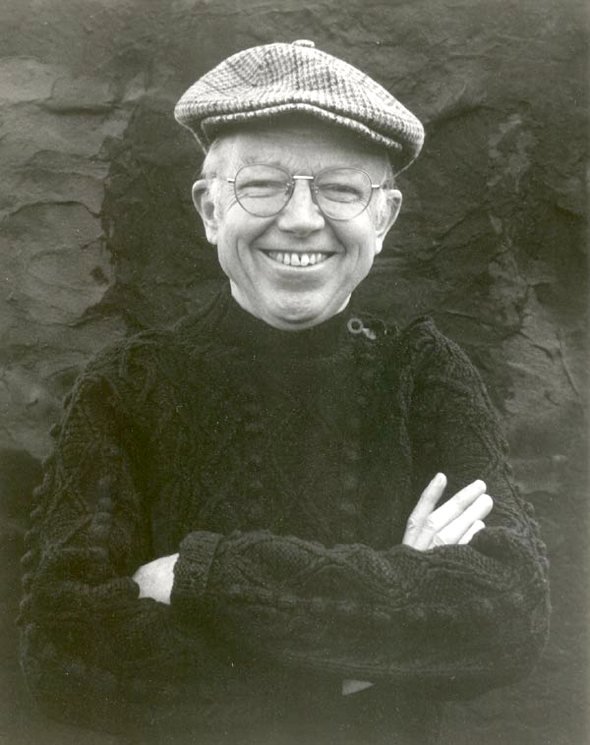

The cinema Parthenon has little space for players who provide ‘assists’ or ‘set-up one up’. George Stoney, the crucial bridge between the old world of traditional documentary and today’s world of social ‘documedia’ or ‘vernacular video’, is one such. Stoney, who has died aged 96 in New York, made over 90 documentaries in more than 60 years.

He worked mainly in the tradition of socially engaged filmmaking established in the 1930s, but he was never primarily interested in film for the sake of film as most practitioners were (and are). The rhetoric of social concern (as John Grierson himself put it) “to command, and cumulatively command, the mind of a generation”, however genuine, usually takes second place to the desire to be filming.

For Stoney, it was the other way about. A Southern evangelist’s son, he truly believed in a vision of activism through media with a low-stated persistence – a sort of secular echo of the religious environment in which he was raised. He was not a documentary social activist but a social-activist documentarist.

So the Direct Cinema revolution of the 1960s, with its insistent focus on the filming process and its strident claims of objectivity, meant little to him. His practice remained meticulously old-fashioned, but his broader agenda of using the moving image as a tool of social action has turned out to be (as can be seen in today’s multiplicity of new platforms for documentary) more significant than Direct Cinema’s claim to be a ‘fly on the wall’. Doing political things at a local level with moving images was what interested him. And he was ever ready to embrace technological developments which encouraged that possibility.

More than 40 years ago, while at the Canadian National Film Board, he began distributing to activist and community groups the first widely accessible video system, Sony half-inch recorders and cameras.

Returning to the States in 1970 to teach at the New York University film school, he became a central figure in the public-access television movement – lobbying US cable firms to make space available as the price of their municipal contracts; training the citizenry to take advantage of the provision; gathering footage with the new gear himself.

But all this, and the 40 years’ of NYU film students who had his social conscience and patient care as an inspiration, was for the Parthenon nothing more than an assist, setting up goals for the documentary so others could take the glory.

In fact glory as a filmmaker was never the prize on which he had his eye, either for himself or for those he inspired. Stoney was, he said, “a happy collaborator”. He was always looking to give others a voice, wanting to find ways “of encouraging public action, not just access”. He was talking about access television but, in general, moving-image technology was for him “how people can get information to their neighbors, and their neighbors can get out on the streets to organize.”

He was born in Winston-Salem, North Carolina in 1916. (His ancestors had emigrated from Aran in Ireland, where Robert Flaherty shot his documentary classic Man of Aran in 1934. Stoney was to make a film about Flaherty’s time on the island: How the Myth Was Made, co-directed with Jim Brown in 1978.) It was touring the rural South as part of a post-war black voter registration drive, screening the 1938 Pare Lorenz classic The River, that Stoney became convinced of film’s power to motivate.

His own career as a filmmaker began in the late 1940s. All My Babies (1953) was a training film made for African-American midwives on location, under the baleful watch of the Klu Klux Klan; but it so exceeded its brief in its warmth and humanity that it was added to the canon of the Library of Congress’s National Register of Film in 2002.

The Weavers: Wasn’t That a Time! is a film of a reunion concert with the pioneer radical folk group (engineered and produced by Stoney, directed by Brown) which became something of a perennial on US Public Television.

For another video, Stoney dubbed a wave of strikes in the cotton mills of the South The Uprising of ’34 (1994) and got a memorial erected to strikers murdered by the company goons. With his last long-time collaborator David Bagnall, he finished Flesh in Ecstasy: Gaston Lachaise and the Woman He Loved in 2009, aged 93. He retired from the classroom last year (at 95).

Look Stoney up or try to buy DVDs of his work and you’ll find little. But his legacy will persist as the goals he set up for the documentary will long continue to be scored.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.