Web exclusive

Vanishing Waves

I first attended the Karlovy Vary Film Festival in the late 1970s. Soviet cosmonauts were guests of honour and the representative for the trade sheet Variety claimed it wasn’t a real festival since there were no Hollywood stars.

|

Karlovy Vary International Film Festival June-July 2012; Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic |

Things have moved on since then, with lifetime achievement awards regularly given to international names. This year it was the turn of Helen Mirren and Susan Sarandon, while the festival’s highly inventive trailers drew on skits featuring past luminaries such as John Malkovich, Harvey Keitel and Jude Law. Typically the festival’s awards (the Crystal Globe) are handed out with self-deprecating references to an obscure town somewhere in the Czech Republic.

But of course Karlovy Vary (Karlsbad) is anything but obscure, even if the nearby Marianské Lazné (Marienbad), where the festival was founded in 1946, survives in cinematic imagination mainly through the work of Alains Robbe-Grillet and Resnais. Karlovy Vary’s past life as one of Europe’s premier spa towns lives on through the tangible reminders of former visitors – Beethoven, Goethe, Schiller and Peter the Great, among others.

Sunshine in a Net

This year’s festival itself was suitably wide-ranging, its retrospectives providing excellent opportunities to review the work of Jean-Pierre Melville, Reha Erdem and Antonioni’s documentaries. There were restorations of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, The Firemen’s Ball (1967) and Slovak director Štefan Uher’s Sunshine in a Net (Slnko v sieti, 1962). This remarkably inventive portrait of the life of young people in the Slovak capital of Bratislava uses impressionist effects and ambiguous symbolism to create a film unique for its time. Undoubtedly the first film of the 1960s Czechoslovak New Wave, it certainly deserves its belated exposure.

I spent most of my time exploring the festival’s ‘East of the West’ competition, devoted to countries of the former Soviet bloc, a section that often outdoes the main competition in interest.

The House with a Turret

While Russia was notably absent this year, the main award went to Eva Neymann’s Russian-language Ukrainian film The House with a Turret (Dom s bashenkoy, 2011). Based, like her first film At the River (U reki, 2002), on a story by the Jewish Ukrainian writer Friedrich Gorenstein, it’s a powerful and original work. Gorenstein, a friend of Andrei Tarkovsky, co-wrote the script for Solaris, and House with a Turret (first published in 1964) was one of Tarkovsky’s unrealised projects.

Gorenstein’s father ‘disappeared’ during Stalin’s pre-war purges and the partly autobiographical story records part of the young boy’s experience during the journey home after his mother’s fruitless journey to Moscow. Strongly empathic, the film adopts a child’s perspective on the war, with its black-and-white images by Lithuanian cameraman Rimvydas Leipus achieving both a poetic and documentary quality. Neymann found her lead character, the nine-year-old Dimitriy Kobetskoy, in an orphanage in Odessa. House with a Turret is a work of imaginative identification, and Neymann’s commitment to Gorenstein’s work is something of a mission.

Made in Ash

If women directors were absent from Cannes, there were two others of note ‘East of the West’ – Iveta Grófová, from Slovakia, and Kristina Buožytė from Lithuania. Grófová’s Made in Ash (Až do mesta Aš, 2012; film homepage), about a Slovak Roma woman working as a migrant worker in the Czech Republic, combined a Loachian and Formanesque opening with animated interludes (she trained in both animation and documentary), providing a powerful and unusual take on a too-common social problem.

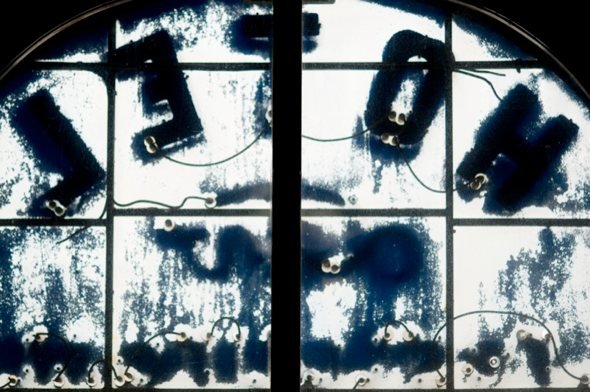

Buožytė’s film Vanishing Waves (Aurora, 2012, pictured at top) – which won a special award – was an unusual SF account of a male experimenter’s attempt to establish mental links with a woman suffering coma. While remaining a genre movie, it was enlivened by an imaginative approach and ambitious special effects.