Alan Parker on set of Angela's Ashes (1999)

Death row

MP: What does it feel like at this stage? The movie’s finished, the American critics have had their go at it, you await the results here… What are your feelings at present?

AP: It’s hard when you make a movie. It’s two years of your life. I’ve been working on it every day for two years, and I’m still doing that. I’m very proud of it. I worked hard on it. You do your best, and people can respond to it one way or another. But you do also wonder whether you should continue.

MP: Continue as a director, you mean?

AP: I don’t know. In the United States, they were pretty brutal about the movie, actually.

MP: What was the objection to it; the main line of criticism?

AP: The main line of criticism is that they don’t really want someone from outside of the country criticising their country right now.

MP: It’s not the first time you’ve done that.

AP: No. But I never think of myself as an outsider. Ever since the beginnings of Hollywood, people have come from elsewhere to make films there. I’m not the first to do that. Two years ago, you start a film… George Bush wasn’t even President then; there wasn’t a question of whether the country was going to go to war or not. You start the film, they set the dates for its opening, then it’s seen to be very critical of a particular institution within the country…

MP: It has nothing to do with their going to war, though, has it?

AP: I don’t know maybe they just hated the movie.

MP: Let’s just talk about the way the film happened. It started with a strike, didn’t it?

AP: What happened was that there was going to be a strike of both actors and writers, about a month apart, and everyone was worried there might be a strike for a whole year. So everyone got kind of manic about finding what they were going to do (before hand), myself included. I’d already read about 200 scripts that previous year, and I couldn’t find what I wanted to do. First, there was going to be a pre-strike movie. Then there wasn’t a strike. You get delayed. That’s why it takes so long. I look back and think I’ve made fourteen films in 28 years, and think I should have made more, maybe. But then you realise there’s always something that holds you up.

MP: But this script had been around for some time, hadn’t it?

AP: It was written in 1998. It was developed by Nicolas Cage’s company for Warner Bros. Then it had been put on a shelf, quite frankly. It had gathered dust. So when I was looking for something, I told them to just send me anything they had. I didn’t even care if it was the sort of thing they’re not doing in Hollywood right now. Then when I read this script I couldn’t believe that something of such intelligence would not have been made. So I got it away from Warner Bros, sent it to Universal, and Universal said they’d like to make it. I can’t imagine how many scripts there are still sitting on shelves…

MP: What was it about this script that appealed to you? I suppose the wider question is, What is an Alan Parker film? But what attracted you to it?

AP: I usually react against what I’ve just done before. The film I’d done before was Angela’s Ashes. The thing is, I started with Bugsy Malone, which was like a ridiculous pragmatic exercise to try and get any kind of film done; and then I did Midnight Express. And they were such opposite kinds of film that it sort of set me in a pattern of doing different things each time. I didn’t do what they wanted me to do, the kind of film they asked me to do all the time. I try to do what I do, but I have to work under the Hollywood umbrella.

So to find a script which was a thriller…. You can’t be pretentious about it, this film got made because it’s a thriller. The studio wouldn’t have done it with regard to its political subject matter. So, to make a thriller that happened to be about something: I thought that was a pretty good fusion. It’s not so much about genres, as about a fusion of possibilities for me to be creative, and to try and make it happen. I’ve always said we’re like guerrillas on bicycles: you steal your art away from hollywood. You give them what they want, and I do what I want.

MP: How central to the process of getting the film made was the casting of Kevin Spacey?

AP: I sent them the script, and the next day the head of the studio said, Yes, I’d like to make it. So that’s great Do we get paid now? And no, you don’t. Because of the strike, they put us on hiatus. Which, when I looked it up in the dictionary, meant there was something lacking, or a gap of somekind. (What was lacking, actually, was that we weren’t getting paid…)

The studio’s interested in three things. What is the script? How much is it going to cost? Who’s in it? Increasingly, these days, who’s in it is very important to them. So until you cast your main star, they’re not secure about what you’re doing. They’re really not interested in me, the director, or the subject, or anything else, quite frankly.

MP: How did you get on with Spacey? He’s a very interesting actor, isn’t he? Another observation is that you rarely work with the same actor twice, do you?

AP: No, I don’t. It’s odd.

MP: Is that because they don’t like you, or what?

AP: Some of them don’t like me. I don’t like them, either. Spacey, I do. I’d make another movie with him. I was talking to John Hurt about this the other day. He’d done Midnight Express, a very early film that I did, and he was saying, You’ve never employed me again. And I said it’s a silly thing you only ever imagine them in the role they played for you. And for them to be in another role, in another story, it’s almost like you denigrate the work that went before. I know it’s silly, but that’s how I’ve always thought.

Would I work with Gene Hackman again? Absolutely, of course. But I’ve got to stop him being the character in my head in the movie I’ve already made with him. Other times, of course, you work with actors that you’d never want to work with anyway…

MP: Who would they be?

AP: What a question…

MP: OK, maybe we’ll come back to that. Let’s talk about this movie. The other thing that was interesting in the casting was Kate Winslet, playing an American. Why her for that part?

AP: She got a script very early on. I didn’t send it to her, but she phoned me up and said she’d read it, and wanted to do it. I said it would be a bit difficult, as the studio wanted an American actor. Like Nicole Kidman… ha, ha. It’s true, I swear to you that’s the truth.

They thought of Kate as someone in corsets doing English movies. So I pointed out that she actually played an American in Titanic, and that that had been a reasonably successful film. But it was a hard sell, as they really thought of her as English. I told them she’d play it as an American, but they seemed to think she’d play it with a Reading accent, when she’s supposed to be a New Yorker. But they finally went along with it.

It’s attrition. They want their people; they give you a list of people they’re comfortable with it’s totally to do with box-office and you end up either with the people you want or you end up being fired.

MP: What about the location? This is a part of the world you’re very fond of; you’ve revisited it time after time. Not Texas particularly, but the South of America…

AP: You pinch yourself you’re so lucky you can make films; that you can go to places where you would not normally go. Did I know Buenos Aires before I made Evita? No, I didn’t. I didn’t know Philadelphia when I did Birdy, or New Orleans before I did Angel Heart. You go to the place and absorb it.

There’s something exciting about going to a place you don’t know. You learn about the place, meet the people, become part of it; and that place becomes almost another character in the film. People ask me why I don’t make a film in Islington, which is where I come from. But it’s as if I know it too well…

MP: But you do keep returning to the same area. What is it about the American South?

AP: It’s very strange. It’s different. Each place is different. Every state in the United States is different from every other state. That’s what’s so wonderful about the States. I’m interested in its magnificence and its diversity and its flaws. Every time you go to a different state you learn something that is not necessarily the cliché. Every state has its own identity, and Texas is totally and utterly different from any other place in the USA.

MP: You’d have had a much more difficult time getting the prison authorities to co-operate in this country than you did in Texas. It seems to me that they opened their doors for you. Would that be true?

AP: Well, they do. Because they encourage films to be made in the States. One ofthe problems here is that if you try to shoot in the streets of London, you’ll have the entire police force telling you you can’t. Whereas in NewYork maybe because you pay the police they encourage you to be there because you spend a huge amount of money. When we arrived in Austin, we went the normal route. You go to the Film Commission, which is attached to the Governor of Texas, and they want to help they encourage you. In this country they just don’t want you there.

MP: Yes, that’s fine in the normal course of events. But what about a movie like this, where you’re dealing with a very contentious subject? Dealing with the death penalty, in a state that’s already been criticised many times for its record. In fact, how many people has it executed?

AP: Well, 1976 was the year the Supreme Court actually allowed for the resumption of the death penalty. Since then, in Texas, it’s about 290. Running now at about one a week, so I can’t give you an exact figure. It’s more than twice the total of any other state, though, obviously.

MP: And how many are waiting on Death Row?

AP: Actually, very few in Texas for the reason that they’ve been executing them. The biggest Death Row is California. There are over 600 men on Death Row there, yet they’ve only had about ten executions in California since 1976. It’s just that the Texans got on with it…

MP: Did you visit the execution chamber?

AP: I did. I didn’t want to, because it’s not actually in the film. We were allowed outside; we shot outside all the prisons; and they were very helpfulto me. But we couldn’t go in. They don’t want a 150-strong film crew around a high security prison. But I had to replicate the cells, for the scene with Kevin where he walks towards the death chamber. So I went there in order for us to absorb it, knowing we had to recreate it.

I didn’t want to go in there. I just found it too horrific, frankly. But I found myself there the warden took me round. They are so open, and so affable, really. They’re not embarrassed that they’re actually leaning on the gurney. They’re not exactly making jokes about the thing, but they’re just so very comfortable with what they do.

Even the PR guy, who has to be there for every execution: he’s done over 140 executions. It seems on the surface that he’s not affected by it. I can’t believe he’s not. But they say that it’s the Law of Texas, the Law of the United States, and while it’s the Law they’re doing their job, and doing it as efficiently as possible. They’ve become inured to it; and in a funny way you do, too, when you walk around it. It’s just a room with a gurney, and you think, well, someone died there yesterday…

MP: It’s a hell of a job description, isn’t it public relations officer to a death chamber?

AP: Because so many people are interested in Huntsville, it’s like Wembley Stadium (or would be…). There are places for people’s computers; they really make it easy for journalists to be there. They don’t hide away from it, because in a way they believe in it. And by making it high-profile, even if it’s critical of what they’re doing, they don’t mind. They’ve made the decision that everybody should know that this is what they’re doing. So you need a PR operation. It’s not just one man. This is an entire machine, like a movie studio’s publicity machine. Very efficient, and very sophisticated.

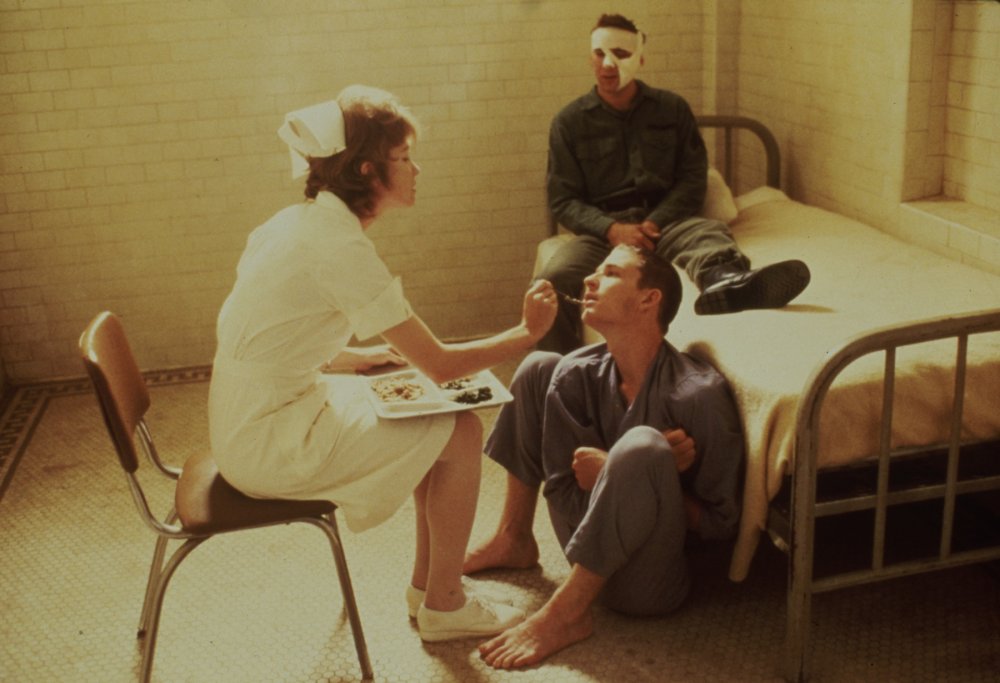

Matthew Modine and Nicolas Cage in Birdy (1984)

500 pieces

MP: Can we move on now and look back at some of your career? Because this is, what, the 14th film you’ve made, isn’t it? They’ve all been very different, all have very strong stories, and very often a moral issue alongside that story. You mentioned Nic Cage there, and in fact he played a part for you as a very young actor in Birdy, didn’t he? What attracted you to that? On the face of it, that was a book that was unfilmable, wasn’t it?

AP: Funnily enough, it came to me as a screenplay, and then I read the book. The book was set against the background of the Second World War, and the people who’d written the screenplay had moved it to Vietnam, to make it slightly more relevant to that audience at that moment in time. I remember going into the film studio at that time, saying I mustn’t swear I’ve got a film about a guy who (euphemism, euphemism) falls in love with a canary in his dreams. And they looked at me as if I was crazy. Yet for some reason they gave us the money…

[Clip — Birdy]

MP: What are your memories when you look at a clip like that, from a film that was made a while ago?

AP: It makes me feel sick, seeing it so close… I think it’s a very good sequence. We had to simulate the flight of a bird. Now, one of the most effective modern inventions in cinema in the last 30 years has been the Steadicam, which is now used in every movie. It was invented by a guy called Garrett Brown, who comes from Philadelphia. He invented the system where the camera’s strapped to your body, and there are a number of gyros and so onwhich give you a smooth track. It’s actually attached to a person rather than on a dolly, and it’s the most-used instrument in modern cinema.

Garrett made a lot of money out of it; in fact, he won an Oscar for inventing it. I’d worked with him on Fame long before this time, and he told me he’d now put all his money into another new invention, called the Skycam. This was a camera on wires held by four cranes and controlled by computer, that we slung over this whole quarter-mile section of Philadelphia. It was his great new invention he said this camera will fly. It has now actually become the usual camera to be employed at all major American sporting events; but at that time it was very much an experimental camera.

Anyway, a week before we did this sequence, Garrett said he was off to Australia on a lecture tour. We should have been suspicious then. This was supposed to be one single, unbroken flight of this camera, over and around an entire choreographed area of Philadelphia, with extras here, and streets there, and cars… It took four days to do. Then on the second or third shot I had to drop the camera so it goes down on top of the car, and then it comes out of that, and goes up to end up on the bird. I was looking at this on the monitor, and it was too slow. So I asked them to do it faster. And they overrode the computer. We’re all gathered round the monitor, watching the camera go down, and suddenly it hits the ground. It broke into like 500 pieces, and we just watched it disintegrate.

We’d spent so much time and money to do the shot, and the camera assistant says to me, Alan, it’ll never work as a shovel…So, we had to think on our feet. There are about 30 seconds that survive from the Skycam, at the end of the sequence, but the rest of it had to be re-made with the old Steadicam. People running with it, on bicycles, webuilt ramps we had to think on our feet. So now if you look at it, you don’t see that, obviously. But that’s my memory of it.

MP: Where do you place that in the list of movies you’ve made? What do think of it when you review your career?

AP: I enjoyed making it. It’s strange, you know. Each film is so hard to do. Not just for me; for anyone who makes a movie it’s difficult. Long hours. We work a 14-hour day when we’re shooting, a 6-day week; and you do that continuously for three months. We’re not unusual; everybody has to make their films that way. So actually to be clear about what you’re making, what you’re doing and what you’re trying to say, becomes secondary to fatigue. Because it’s really, truly hard.

In the great days of Hollywood, they would work from 9 to 5, get in their cars, drive over the hill, and they’d go home. We don’t these days. Because over the past 30 years, film-makers like myself choose to be in the real place; to be in the streets. It’s infinitely more difficult. So when you look back on any film of mine, or at any clip you show, you remember how hard it was more than anything else. None of them were easy.

MP: You said earlier that there were times when you questioned whether you should continue. There was a point, I believe, when you really did contemplate giving up and going back to writing, didn’t you?

AP: Well, I’ve always written. It’s nicer. If you write, it’s just you. Film is a totally collaborative art form. I make a film with 150 other people. I’m the one who guides them. I quite like the cameraderie of the film set; it’s the one thing I’ve always enjoyed. So I keep coming back to it. But it’s a much more civilised life to sit there at your computer and write, of course.

MP: Wouldn’t you miss the control of it, as well? In the end, you are the ring master.

AP: No. I’m the one with the biggest mouth and the American Express card.

MP: You’re the guy who pulls it all together. That kind of power and control is absolute, isn’t it?

AP: It is, for good or ill. My films end up the way they do because of me. if people don’t like them, it’s my fault. I don’t blame it on to the film studios or anybody else. Because I’ve lived a charmed life. I’ve been in absolute control of my work, even though I work in a very difficult area ofthe Hollywood machine. They’ve not interfered with what I’ve done, and therefore if they end up well or if they’re not liked, it’s no-one’s fault but mine.

MP: One of the most extraordinary things about your career is the way you’ve been able to maintain your independence. There must have been moments when you thought it would be much easier to play the game a bit more?

AP: That’s true. If I’d have made the films they wanted me to make, it would have been easier. And I’d have been a lot richer.

MP: Let’s talk about one of my favourite movies of yours, Mississippi Burning.We’re going back to the Deep South here, aren’t we? This film, of course, caused a stir in America. Black activists said it portrayed the Civil Rights movement as consisting of white activism only, and missed them out. Did you miss that point when you were looking at the movie, or did you not think it mattered in any case?

AP: If anyone’s seen the film, the loudest voice in it is the black voice. It just happened to have been made by a white person, and in order for it to be made at that period of time, it’s about two white FBI agents who go down to Mississippi. With regard to whether it’s the definitive film about the black Civil Rights struggle in the South No, it’s not definitive in any way. I thought it would help other films get made; and many films were made because we made this first.

But when the criticism came, most black organisations were in fact arguing amongst one another. Some were for it, others against. Some people didn’t want to be reminded about how difficult things were for black people during that time, and to see it was something that was not acceptable. It was to do with political correctness and everything. But in the end, I’m very proud of it. The actual story was about two white guys and a black guy who were murdered. That’s the true story one of the most famous of the beginnings of the Civil rights struggle. That’s what the movieis.

[Clip — Mississippi Burning]

MP: A very powerful opening, that, isn’t it? One of the problems of being a director is that you can look at any sequence you’ve made and pick the bones out of it. But, looking at that, I don’t think there’d be much you’d want to change, would there?

AP: Not really. It was filmed over four nights, the whole thing, and it has to mesh. It’s always tricky when you shoot it over a long period of time. And it’s always very peculiar when you see your film, not having seen it for along time.

Mississippi Burning (1988)

Can’t sing, can’t draw, can direct a little

MP: What about the business of making movies? You didn’t go to film school. I believe you’re totally self-taught in a sense, aren’t you?

AP: I think most directors are. The best place to learn is at a film school, obviously…

MP: Is it?

AP: Well, if you ask any film-maker how they got into it, everyone came a different route. I’ve never actually watched another director work. I know that everybody says ‘Action!’, and everybody says ‘Cut!’, but that’s about as much as I ever knew.

MP: But if you’re asked to explain to a group of students, as no doubt you are from time to time, how to make movies, is there not a lot you can say because it’s instinctive in the main?

AP: I always used to believe that you should be a film director because you’ve got something to say, and you’ve chosen this way of actually communicating with people. It’s often not that way now, because many young film-makers are interested in the process. Because films have become much more technical, and it’s a computer world out there now. So it’s not merely about what they’re saying, it’s about how they’re doing it.

I’ve never really thought that was the really important reason. But I do believe that, in the end, I came to it as a writer; because it was an extension of my writing. Instead of words, it’s up there. A very powerful way to communicate to people. That’s how I came to it, but talk to any other director and they’ll have come to it by a different route.

MP: Powerful, yes. But does it change anything?

AP: No. You can affect… I can’t change people’s minds. I only have two hours to talk to anybody in the audience about whatever my particular point of view is. So all I can do is provoke debate. The films that I do tend to polarise people’s views. But hopefully people will talk about the film when they leave here. That’s the most I could ask for.

MP: Just on that theme… I think you’ve made quite clear your view on the death penalty. Was it a view shared by the rest of the cast?

AP: Not necessarily, no. It might have been. Their position is more guarded. It’s perhaps ironic that Kevin speaks out about almost any other political subject, but not on this. He feels they’re actors, and questions whether you should know too much about someone who’s an actor. Because this is the time of the celebrity, with everyone wanting to know every single little thing about someone.

And Kevin, and Laura, and Kate, really feel actors should be like blank paper. They want you to believe in the character or the role. Do you want to see Kevin Spacey as an advocate, or playing the role? So actors are a litle bit more guarded. It’s different for me as a film-maker. I’m very much against it, and I hope that’s what comes through in the film. It’s harder for them as actors.

MP: OK, let’s now look at another movie, which again I’m very fond of. Probably my favourite The Commitments. Where does it rank in your estimation?

AP: Well, it was the most fun to do. On some films, you wake up… This film I was pleased to make.

[Clip — The Commitments]

MP: That film had a great exuberance and a great freshness about it, didn’t it?

AP: It did. Which came from the kids that I cast, who were brilliant. Most of them hadn’t acted before. I used to wake up in the morning, and I couldn’t wait to get to work.

MP: You work well with children, don’t you? Right through from Bugsy Malone, you’ve done quite a few films with them. What is it about them? Is it a fresh canvas? Is it that they’re not actors?

AP: I think you get things that I can’t put in. The magical things come from the people themselves. And they’re less aggravation than movie stars, yes.

MP: Which leads us naturally on to Evita… and the question I’ve been saving up for you about actors. It’s been my experience over the years doing my chat show, not that actors have necessarily become more difficult, but that the baggage surrounding them has become larger: the entourage is bigger. It’s more aggressive, more intrusive. That’s my experience Would it be the same from your director’s perspective?

AP: It’s funny. When you get people on your show, a lot of the time they’ve got like a movie, or a book, to talk about, and are therefore part of a publicity machine. These kids were quite extraordinary. We took them to America and they couldn’t believe their luck, that they had a thing like a limousine, or they had people like publicists fussing over them. So the publicity process is where they’re spoiled, rather than when they are making the film.

You have actors who live in a motel in the middle of Texas, like we had to when we were making the film, who go to work in a bus with ten other people, as we all do. But the moment they begin to do chat shows like yours, they’re going, ‘Where’s my limo?’ And they start to claim that their room at The Dorchester isn’t big enough. It’s strange. It’s really the publicity side, rather than the shooting.

This lot were the funniest because we took them to America, all twelve of them. They’d have twelve separate rooms, and they couldn’t believe like how many of them could get into a limo. But in the twelve rooms wherever they were, all across America promoting The Commitments the hotels had never had an experience like it there’d be twelve rooms and twelve empty mini-bars. Empty of everything, that is the Toblerones as well as the booze. They were great, and the publicists liked them because they behaved like decent human beings, which in the end is all you can ask for.

Of course, as you know, when actors are promoting a movie, they’re not actually paid for that work. Sometimes it’s in their contract, so they can be pressured. But, actually, if they’re not good at it, or they’re not David Niven, then it’s a pain. I mean, your show may be easy to do, but it’s not so easy when you’re doing it in Germany or Bechuanaland or wherever we’re sent. And because they don’t get paid, they start to behave rather badly…

MP: But what about a project like Evita, and what about a star like Madonna? Who comes from a different perspective she’s not basically a screen actor, she’s a pop star.

AP: She’s a complete and utter nightmare in so many ways. But for me she was a complete professional. She really worked hard on that film, and whatever people think about her as an actor it’s very easy to be snidey, as the British are, of course but she’s pretty great in the movie. I don’t think anyone else could have done it as well as she did. No-one could have worked harder, and no-one could have given more to me as a director.

I worked with her for four months in a recording studio before we even went on to a filmset, because we had to do all the music before hand. If you ask the make-up, and the hair, and the first assistant directors, they might have a few other things to say about her. But she was very nice to me.

MP: How much does working on something like that sung through as an opera how much does the music dictate the way you direct?

AP: Very much so. Because I had to make dramatic decisions while we were doing the music, before we’d even got to the film set. I was there for all of the music, to pre-record it. Should it be projected? Should it be quiet? Where will the camera be? I had to think about what was, in fact, an opera. It’s hard, because it’s not a form that’s done very often on film, and difficult to pull off.

[Clip — Evita]

MP: It must be wonderful to mastermind a spectacle like that.

AP: Well, you have a lot of help. I storyboarded the whole thing, based very much on the original funeral. So you have that to go by. Then you have this army of people there are four-and-a-half thousand extras there, all in period costume. They started to get them ready at 3.30 in the morning, and we were ready to shoot at 10.00. Which is quite extraordinary. That was shot not in Buenos Aires, but in Budapest. They put the whole thing down the end of a street, and I called, Action!, and the whole thing came towards us. That was my contribution, actually.

MP: I was going to ask you about storyboarding, because you are a talented cartoonist. When Tim Rice and I had a publishing company, we published your book of cartoons.

AP: Most of your books failed to make any money, but this one made even less.

MP: Yes, we are ex-publishers because it didn’t work, but yours was spectacularly a non-seller… It may have had something to do with the size of the book. I don’t know why we did it, but it was about the size of the palm of your hand, wasn’t it? It was called Hares in the Gate I think people missed it because they couldn’t see it.

AP: I think they figured out that I couldn’t draw, as well.

Sir Alan Parker with Madonna on the set of Evita (1996)

Free lunch to go

MP: Let’s now take some questions from the audience…

Q: Did I see you in the film tonight?

AP: Yes, you did. I was the greedy neighbour, stealing the baguettes. You do these things. It was late at night, maybe 3.00 in the morning, after we’d had our snack, and had had too many glasses of wine, and you try to amuse the crew, who are very bored by that time. So it was time for my cameo. The kind of Hitchcockian thing you do to humiliate yourself in front of the crew.

MP: Is that the first time?

AP: I’m actually in most of them, I’m embarrassed to say. You try to do it without being spotted. But at the NFT, they always know exactly where you are.

Q: I understand you had a contentious relationship with Roger Waters on The Wall. Would you comment on that?

AP: Actually, anybody who knows Roger you can’t say hello to him without being contentious. He is very brilliant, and The Wall was his idea, his baby, and I worked with him and Gerald Scarfe on putting together a blue print as to how we might shoot it. Then it was very difficult so I said that if I was going to direct it, he’d have to go away. He was very good he did go away while we shot it. Then he came back when we had to mix all the music, which he had to be there for. He wasn’t easy. And of course he’s no longer part of Pink Floyd; so you should ask the rest of the band if he’s contentious or not.

Q: Is there any conflict between your roles at the BFI and now the Film Council, and as a film-maker?

AP: Errr…

MP: Are you an establishment figure?

AP: Yes, I guess so.

MP: Sir Alan Parker now?

AP: Yeah, thank you…

MP: No, I’m delighted. I look forward to you being Lord Parker.

AP: Yeah, funny. Imagine the reviews I’d get then.

MP: Conflict?

AP: There isn’t, really. The work that I have to do for the Film Council is about what other people do rather than what I do. The only difficulty is that whereas I usually make a film every two years, in the past eight years I’ve only made three. So by doing those jobs, I probably missed out on making one movie. That’s the only way it really affects me.

MP: It’s the old hoary question the British film industry. Have we got one? Do we deserve one? Do we need one?

AP: I think you’ve answered it there…

MP: I mean, you’ve made 14 movies, and I think only three have been made in this country, haven’t they? I would imagine that’s because you go where the money is?

AP: I go actually because I’m attracted to American stories. Otherwise, why don’t I make a film in Islington or Manchester or wherever? Is it the money? Well, could I get $40 million to make this film here? No. It’s not what I get paid; it’s to have the full tool-kit for what you do. I saw Ridley Scott in Los Angeles last week, and I said I’d got absolutely slaughtered by the American critics for The Life of David Gale. He said, why was I worried about it because Ridley gets slaughtered all the time, too Just tell them how much you got for doing it, and that really pisses them off…

MP: How much did you get for doing it?

AP: Too much.

Q: Where do you go from here? Where do you go next?

AP: I kind of agonise over what to do next, every time. I don’t come to a decision until I’ve finished the film. I do think you react against what you’ve just done. If you’ve done a serious film, you can end up with something lighter, possibly. So I really don’t know. Some directors have a drawerful of screenplays, and I never do. I’m quite monogamous to one film. When it’s finished, then I think about what I should do next. That’s the process I’ve always followed. When you start doing it you feel embarrassed everyone always has their next film lined up, and I never did. I have written a novel, though, that’s coming out in November. That’s what I’ve been doing.

MP: What kind of a novel is it?

AP: It’s a good one…

MP: Is it about the film industry?

AP: No, not at all.

Q: When you’re starting a new project, are you first caught by the story and the words, or by the images?

AP: I think story first. A screenplay is about words, obviously; and the story is what you want to say, first. The images do come later. I had to storyboard the Eva Peron funeral because it was so complicated and so many people needed to know what shots I was thinking about. But mostly I don’t do a storyboard. I know some directors do.

Steven Spielberg has a big book, calls it the Bible, and everyone has to copy that shot. He gets a guy in who’s a very good illustrator, who comes and does all these drawings for him. Then he knows what he’s doing. But for me the images come much later. Even when I’m writing, if it’s a screenplay of my own, I can imagine a scene I can maybe see you sitting there, and as I’m writing I can have a very clear view of how the light falls on your face, how you’re sitting and how you’re holding your face in your hand. But when I come to actually shoot it, something else happens, which is so totally different.

It seems to me that a director’s job is to look for wherever the magic may be in any scene, and sometimes it’s not where you think. It could be in another character, close on their eyes and you only know that when the magic of rehearsing and shooting it happens. So to have some sort of preconceived idea of how a shot should be I don’t think any director ever is that clear about what it is they want to do. Sometimes the images in your head are better than what you end up with; sometimes they’re nowhere near as good as what happens in front of you.

Q: Do you ever envisage crossing over to work in the music industry?

AP: No. There are certain things I do where there’s an overlap into music production. I produced most of the music for my films. My sons composed the music for this film, which was quite nice. One, they were very cheap; and I was going to say they did what they were told, but it was actually the opposite. It had been easier working with John Williams.

MP: Your wife produced the film, too.

AP: Yes.

MP: Quite a cottage industry.

AP: I know; ridiculous, isn’t it? But I think my boys did very well. They’d worked with me before on films, but it’s the first time they’ve done the whole score. It’s strange when you do music. With most of the music I do, I experiment as I go along. There are two theories. There’s the Spielberg/Williams theory, which is that Steven gives him the film when it’s finished, and he writes the score to it. John is the best in the world at doing that.

I remember when I was doing Angel Heart, and I went to Rome to meet with Morricone, another great composer. I had music I’d laid all over the place, and he said that he was insulted. He wouldn’t speak English to me, and his manager said Ennio has to have a silent movie; only then will he do the music for it. You’ve already made all the choices, and he doesn’t like that. So there was a great deal of jazz in Angel Heart, which I’d recorded while we were actually in New Orleans. But Morricone obviously thought he could do better in Rome where they’re really known for their jazz musicians…

So what I’m saying is that it’s either an integral, organic part of making the film, which some film-makers like to get involved with I do or you just finish the film and give it to a great composer, as Spielberg does with John Williams. I worked with John on Angela’s Ashes, where it was exactly that process. I’d laid out music all through the film as an indication of what I’d wanted, but then I gave it away. John does it, and stands there in front of an 80-piece orchestra, and either it’s really great or you hate it. You’ve got nothing you can do about it at that stage.

MP: Speaking of Angela’s Ashes: you sent me a video. Should we show this?

AP: Yes, just to lighten up the evening.

MP: It’s a scene from Angela’s Ashes that is set up to illustrate the international aspect of film-making, isn’t it? It’s a scene that’s played over four or five times, but in different languages. Now that seems a rather boring premise, but have a look and see if you think this is boring…

[Clip — Angela’s Ashes]

AP: The Spanish version is like two old men have done the dubbing, and two seven-year-olds; like they’ve run out of people. You dub Italian, Spanish, German and French everywhere else in the world the films are subtitled.

Q: What is your attitude to the plethora of film awards?

AP: Awards stink. Especially when other people win them and you don’t. What really irritates me no end is that the Oscars and the BAFTAs and a few others, together celebrate about ten films. They’re so proud of this, and it goes to about two-and-a-half billion people around the world, that that is the American cinema.

Well it isn’t, actually. It’s probably one per-cent of all the films that come out of that machine that are as good as that, even if you think those are the best. They celebrate it so much, yet most of the films they make are not in that area. They make one a year each, each studio, maybe two, in order for them to qualify for the Academy Awards; and that’s a great tragedy to me. The fact that television companies are so obsessed with these things…

For instance, there’s this thing called the Golden Globes: the most important awards other than the Academy Awards. They’re more important than the BAFTAs because of where they’re positioned in the voting calendar. The Golden Globes are run by an organisation called the Hollywood Foreign Press Association. It’s a hundred people or so, most of whom I’m not sure ever even file foreign articles: anyway, a strange bunch of people. And I go every year, like everybody else, and I have to be incredibly sycophantic because the Golden Globe awards are seen as important.

The main thing is that the studios have to provide a very large breakfast or lunch. I took my wife this time, because she didn’t believe me that the main thing was to watch them steal the food. They’re just wrapping up ten croissants, and they’re out the door. (Of course, that’ll probably be on some internet site or another now, so that’s the last Golden Globe I’ll ever win). No, it’s rubbish, awards. I’ve been very fortunate to win a few. But when you win, you take it for granted you think, quite right, and when you don’t, you just get irritated watching other people get them.

MP: That begs the final question, then. That, in the end, what matters to you, after 27 years and 14 films and with more to come? What is it that satisfies you, and keeps you going?

AP: Well, just irritating the shit out of the critics seems to have been what I’ve been doing. I don’t know. It’s quite extraordinary I’ve been allowed to do it, really. When you make your first film, you do surely believe it’s going to be your last. (Especially after you’ve read some of the things said about it). No, obviously, I love it. I think I’m good at it. I pinch myself I’m so lucky I’m allowed to do it. I don’t think I could do anything else that’d bring me such pleasure.